The grand foyer of the new Metropolitan Opera house at Lincoln Center — one of the famous chandeliers, gift from Austria.

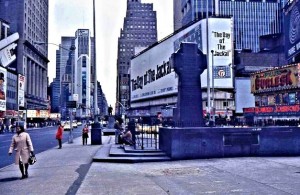

My first year in the New York City area I was very busy with my college and graduate courses. Taking the New Haven railroad to the City every week and wandering through Grand Central Station, walking along the big avenues, Fifth Avenue, Madison Avenue, Park Avenue, more old-world looking in those days — all this opened up a new and exciting world to me. I also did an enormous amount of reading that year and felt that I was really moving on in my life. No stagnation anywhere. I was busy and happy.

When early on in the spring semester I got a tutoring job at Mount Vernon High School, that got to be another new world as well. I had mainly Jewish students. Mount Vernon at the time was said to be made up of three minorities, Jews, Italians and Blacks. I loved my tutoring job with small groups and very motivated students. I used a method I always use in my teaching, the question-and-answer method to get the students to speak.

With my British accent I explained how things were going to be. I ask you a question and you answer. After a very short time, it felt strange to go on with the ‘ahsk’ and ‘ahnswer’ and little by little I slipped over into American pronunciation. In Florida it still today happens that people ask me if I come from New England, even though I don’t sound a bit like a New Englander, but definitely not like a Southerner.

_________________

In the fall of 1964 I was settled in New Rochelle and the world I saw was all new to me and so very different. The residential areas I drove through on my way to Mount Vernon High School, my first teaching post in the fall of ‘65, were not like anything I had ever seen in Sweden. Blooming trees, dogwood and magnolia, and well-kept lawns around pillared white houses. This was the posh part of Pelham.

And there was the huge and wonderful City, not like any big city I had ever known. I got acquainted with the Bleecker Street Cinema and its repertory movies, typically Italian, Swedish, French ‘nouvelle vague’, and the great British comedies that were flourishing at that time.

I found Greenwich Village enchanting and I even had the gall to see the French professor at New York University in Washington Square to ask him if he might have a job for me. I did speak French fluently with a native accent and I thought naïvely that I could possibly do some conversation classes. We had a fairly long and very pleasant conversation, but no job for me. I really had some chutzpah to even try for a job like that.

Washington Square in the early summer of 1973. John and Kajsa in the foreground and the square surrounded by New York University.

Allyn was a New Yorker, but even though he had been a speech and drama teacher in Syracuse, New York, he actually had to be pushed to go to a play in the City. We made it to the theater though after one semester of my just digesting all the new things that were competing for my mental intake.

Our first play was a most spellbinding ‘Medea’, originally by Euripides, in a much lauded new adaptation by Robinson Jeffers. It was at the Martinique Theater on 32nd Street in January 1965, an off-Broadway theater that has since vanished. The star, the African-American actress Gloria Foster, had made her New York City debut in Martin Duberman’s ’In White America’,1 and she made this ‘Medea’ into a heart-breaking experience.

In the fall of 1965 I again brought up the subject of theater and we picked “The Glass Menagerie” by Tennessee Williams, at the Brooks Atkinson Theater. That was real Broadway but it did not give me goose bumps. The main problem was likely the seats Allan had bought. He was a bit stingy and our seats seemed to be a mile away from the stage, up in the balconies. I knew the play vaguely, even though I am not sure I saw our performance of it at Malmö Stadsteater. I was thirteen years old then and I doubt if I did.

There was, however, much talk about it at home and Mother had collected her own glass menagerie which began with a cute but not very graceful glass frog and then went on to a giraffe, a deer and all sorts of more graceful glass animals. In her little salon, she had a mirror-topped low table with very pale brown glass, and so all the animals in her little menagerie were mirrored on her table top.

I didn’t get much out of the performance of ‘The Glass Menagerie’ on Broadway, and I told Allyn I never again wanted to sit in in what we in France call the poulailler, where the chickens roost. I can not get myself immersed in a play if I sit that far from the stage, and I don’t know how anyone else can either.

___________________

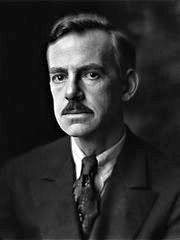

Among the most remarkable plays I saw during my years in New Rochelle was “More Stately Mansions” by Eugene O’Neill. It was directed by the most competent O’Neill director in the United States, José Quintero, the Panamanian-born theater director and producer who had done so much to revive O’Neill’s once fading reputation as a great dramatist after his first successes.

‘More Stately Mansions’ at the ‘Broadhurst Theatre’; Ingrid Bergman as Deborah Harford, Colleen Dewhurst as Sara Melody and Arthur Hill as Simon Harford. (Playbill)

The production that opened at the Ahmanson Theater in Los Angeles in the spring of 1967 moved to the Broadhurst Theatre in New York City in the fall of the same year. Ingrid Bergman played the role of Deborah, Simon Harford’s patrician mother. Colleen Dewhurst, and Arthur Hill had the other two leading roles. The play had its world premiere at Dramaten in Stockholm in 1962 under the direction of Stig Torsslow, the other O’Neill specialist in Sweden, besides Karl-Ragnar Gierow. Stig Torsslow had also been our second theater director in Malmö 1947-1950.

The play had been left unfinished and in an unplayable form of over ten hours playtime. Wikipedia says: “Against his wishes, O’Neill’s widow, Carlotta Monterey, authorized Karl Ragnar Gierow of the Swedish Royal Dramatic Theater to turn the unfinished work into an acting version”. However, I am not quite sure that this is correct. From other sources I have read, it appears that O’Neill changed his mind during the very last days of his life.

Be that as it may. Gierow carried out the tremendous task of trimming the play down to a playable four hours. He had in fact done the same thing for the “A Long Day’s Journey Into Night”, the O’Neill play I saw at Dramaten (as the Royal Dramatic Theater is usually nicknamed in Sweden) in 1956. Gierow was at the time the director of Dramaten and he personally had frequent discussions about those plays with Carlotta Monterey O’Neill, Eugene’s widow.

Seeing the Dramaten production of “The Journey” was probably one of the most memorable theater events of my life. I will never forget the superb actors Lars Hanson and Inga Tidblad and also Ulf Palme, Jarl Kulle and Catrin Westerlund. Bengt Ekerot was the director. I talk about it at some length in my chapter on Stockholm theater. ‘Mesmerizing’ is the word I use in that chapter.

“More Stately Mansions”, which was at the beginning titled “Build More Stately Mansions”,2 was a fine performance, but not as mesmerizing as the Dramaten production of “The Journey” had been . Frankly Ingrid Bergman could never stand up against a superb actress like Inga Tidblad. Of course she too had a magic stage presence, but the whole production was, in my view, not on the same level.

Years later, in Paris, when I told Arne I was not terribly impressed by Ingrid Bergman or by “More Stately Mansions”, he said that to begin with it actually was not that good a play, not as riveting as “A Long Days Journey” or O’Neill’s other plays, which he admired very much. This is of course just Arne’s personal opinion. The play is about the battle between Deborah, Simon Harford’s proud and domineering mother and Sara Melody, his wife, who was an innkeeper’s daughter. They are both battling furiously for the love of Simon and this leads to despair and tragedy.

As usual in O’Neill’s plays, the struggle between classes is a main feature in this play – the aristocracy/peasant opposition, a dominant theme in all O’Neill’s plays and a reflection of the tensions he had experienced in his own family. ‘More Stately Mansions’ is a sequel to the early-American story he began in “A Touch of the Poet”, where Sara is portrayed as a ‘scheming Irish wench’. Even though she is deeply in love with Simon she is also determined to make a place in the world for herself. Deborah has a long and weighty speech where she lectures Sara on her “grasping personality” and “evil ambition”. In fact, the play seems weighed down by Deborah’s overly intellectual vocabulary. This monologue, full of invectives, is considered to be a very central speech in the play, but it would not surprise me if Arne considered the entire play to be fine literature more than good theater.

The world premiere’s taking place in Stockholm was according to the wish of Eugene O’Neill himself as had been the case with “A Long Day’s Journey”. The Royal Dramatic Theater had been the stage for so many of O’Neill’s plays and had been so faithful to his reputation that he expressed his wish that they have the right to the world premiere of his subsequent plays.

___________________

In 1967 Allyn and I saw two very memorable plays of the school which came to be known as the Theater of the Absurd, “The Homecoming” by Harold Pinter at the Music Box, performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company. The director was Peter Hall who made the Company what it came to be. It had premiered in London at the “Aldwych Theatre” a year and a half earlier, in the same staging by Peter Hall. Ruth, the only female part, was played by Pinter’s first wife, Vivien Merchant. Stark theater, but very impressive. It was a great performance , but it did not leave me with an imprint of the kind “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” did – Albee’s stunning play that I find somewhat reminiscent of “The Homecoming”, maybe just because they are family conflict dramas. “The Homecoming” is considered to be a representative example of the theater of the absurd, but I am not so sure that I would count it in with Ionesco and Beckett and other plays by Pinter.

In early ’67 we also saw Edward Albee’s “A Delicate Balance” at the Martin Beck theater, another stark play, but maybe less gloomy than Pinter’s “The Homecoming”. I was not terribly impressed by this play about melancholy and complicated personal relations but it was well done.

The funny thing is that John saw “A Delicate Balance” too. He had just come up from Tallahassee and Florida State University to the New York area with his first wife to work at Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island. They were both musicians and they frequently made it into the City for the opera, concerts or for theater. We kid about how we just might have been sitting right next to each other at that play too, the same as two years later for the “La Mama” performance at Le théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in Paris, where we first met in January ‘71.

I was familiar with le théâtre de l’absurde from the plays “La cantatrice chauve” (‘The Bald Soprano’) and “La leçon” (“The Lesson”) by Eugène Ionesco that had been running at le Théâtre de la Huchette in Paris since 1957. In fact, as far as I know, those two plays are still playing at the same theater today. Ionesco, however, is in a different category from Pinter and Beckett. Ionesco makes us laugh, and he wants us to laugh.

I had also seen Edward Albee’s “Who is Afraid of Virginia Woolf” at Malmö Stadsteater in 1963, a play that is close to this theater that deals with non-communication between people and the lack of meaning in our lives. However, I have never thought of Albee, the modern playwright I consider to be my absolute favorite, as belonging to that school, contrary to what literary critics generally profess.

Albee is Albee. He is himself, different from anybody else. The title of this play is a pun on the song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” from Walt Disney’s “Three Little Pigs”. It is said that Albee wanted to call his play “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” but got a Njet from Disney. Copyright. Hands off. So, tongue-in-cheek, Albee gave his play a title that made no sense whatsoever. I have this information from Arne (however, it also turns out to be general knowledge) who knew a friend of Albee’s and this same man also told him that Albee pronounces his name like “all-be”. In his rejection of his foster-parents and their bourgeois way of living, he changed the way they pronounced their name.

When I read the play with a class at l’Ecole Centrale de Paris around 1980, my most interesting question was at the end of the play. George says: “Who is afraid of Virginia Woolf …?” Martha replies: “I… am… George… I… am…” I told my students to read ‘the big bad wolf’ and not the name of the famous writer. The question is ‘What is she afraid of?’ And in that very final scene the two enemy / lovers are joined again after an evening of destruction and self-destruction. Martha is finally letting George know that she is afraid, afraid of living a meaningless life, and that is why she had invented a fake son that she kept mentioning to the young couple she had invited for drinks that evening. She is finally letting go of fake reasons for living and admitting that she is afraid. Afraid of the naked reality.

Now, all she has is George and her cruel game of putting him down is over. It is very much like a person who suddenly sees that his religion is nothing but an illusion. The next thing you ask yourself is whether the people (le peuple) would create their own illusion of a god and religious morality even if it were not imposed on them from the ruling elite, secular and religious. There are probably few things that serve as well to dominate the masses as religion and all its taboos and rules of living. Moses came down from the mountain with the tablets containing the ten commandments. What a powerful myth this has become for two of our major religions. Islam has also set up ten commandments that are quite similar to the ones we know. Those commandments are all designed to keep people in line, to make them obedient citizens.

But above all, there is the belief in a heaven and a hell, an afterlife where we will once again be with our loved ones and where we will be rewarded for our good deeds in our “first” life. It is obvious what the rulers of the world have to gain from holding out the formidable illusion of a paradise to all the people they are set on dominating. In the Jewish religion there is no belief in an afterlife, and it is a big question in my mind how the religious leaders mange to convince the Jews to live a moral life without the introduction of an illusory paradise as a reward to the “good”. But here I am of course going far beyond what Albee had in mind when he ends the play by the breaking up of Martha’s illusions. However, it would surprise me if he did not have the parallel of religion in mind.

As for the denouncing the platitudes and the triteness of bourgeois living, Albee deals with that more precisely in “The Zoo Story”, which I refer to in Chapter 18 (Part 2) – “Mamaroneck High School and Theater”.

I admit that I don’t remember very much of the play in Malmö, even though the actors were excellent — Olof Bergström and Agneta Prytz as George and Martha. It was overshadowed by the powerful movie in the direction of Mike Nichols, starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

One thing about Albee and his plays that strikes me as a funny coincidence is that I happened to listen to (remember radio?) a play on the Swedish radio probably in 1963 that was very gripping; It was called “The Death of Bessie Smith”. I remembered the title very well because it was so different from any play I had known until then, and it moved me very much. However, I had never heard of the author. Much later I learned that the author of that play was Edward Albee and it was first performed in 1959.

Even though I have nothing of Martha’s personality in me, I can, whenever I see the play, actually identify with her, feel what she feels, even if she is cruel, maybe even sick, she ends up being a little girl who tells George how scared she is. That is precisely what “A Delicate Balance” didn’t do to me. I remained an outsider. i did not identify with anyone in the play.

Also in the late summer of 1966 I saw “Waiting for Godot” by Samuel Beckett with my sister Gun also at Malmö Stadsteater. This is real Theater of the Absurd. I had just seen the play in Paris and the performance in Malmö was so entirely different that it did not seem to be the same play. In Malmö they had made it into a comedy. In Paris it was a bleak story about the nothingness of everything. You are waiting. What are you waiting for? Nobody knows. The meaninglessness of life. Maybe. The play has been hailed as the most influential of all the plays of the Theater of the Absurd. The world has been intrigued by it and other Beckett plays ever since its first premiere at the Théâtre de Babylone in Paris in 1953 –“En attendant Godot”, direction by Roger Blin. Beckett, an Irishman, wrote in French or English, but “Godot” was first written in French and then translation into English was done by Beckett himself.

______________________

The'”Vivien Beaumont Theater”, also called “The Repertory Theater” at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, first opened to the public in 1965. It was there even before the new Metropolitan Opera had its grand opening in September, 1966

Lincoln Center; the Metropolitan Opera left and the New York Philharmonic Hall on the right; later called the Avery Fisher Hall

The Lincoln Center, which was finished by the end of the sixties, virtually changed the face of New York City. The architecture is stunning and everything essential to music and dance can be found there.3

The wonderful sculpture by Henry Moore which is set in a pool in front of the Vivian Beaumont Theater.

In March 1966 Allyn and I saw “The Condemned of Altona” (“Les séquestrés d’Altone”) at the Vivien Beaumont Theater. It is a play by Jean-Paul Sartre that I had never seen nor read. “We” did both “No Exit” (“Huis clos”) and “Dirty Hands” (“Les Mains sales”) in Malmö. I saw “Les Mains sales” and was gripped by it, but unfortunately Mother and Arne did not work at the theater any more when it was performed in 1949, so Mother did not take the pictures for that play. That is a long story that I have talked about in another chapter.

The performance at the Vivien Beaumont Theater was quite impressive. “Les Mains sales” is in fact my favorite play by Sartre, who has never been a real favorite of mine. My hero from those days was and is Albert Camus, both his plays, his intriguing novels and his philosophical books such as “Le Mythe de Sisyphe” and “L’Homme révolté”. When John and I lived apart in 1971 – ’72, John in Paris and I in New Rochelle, we wrote frequent letters and, among other things, we had a lot of fun discussing these books.

The expression Camus uses – “faire le saut”’ – fascinated me. We make a big leap from the attempt to put a meaning to our lives and across the enormous gulf, a leap that takes us to the land of the knowledge that there is no meaning and we live our lives with that realization, open-eyed. Life is ‘absurd’ in its very essence. Quote: “La liberté naît de la découverte de l’absurde qui permet à l’homme de tout voir d’un regard neuf, débarrassé des habitudes et des préjugés, et d’observer lucidement sa condition sans espoir ni lendemain. La passion permet de multiplier les expériences lucides … Sentir sa vie, sa révolte, sa liberté, c’est vivre et le plus possible.“4

However, what has impressed me the most of the works by Albert Camus is L’Etranger (“The Stranger”). The opening words by Meursault, “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas.”5 move me profoundly. The end of L’Etranger is the most absurd piece of writing I have ever encountered anywhere: “J’ai senti que j’avais été heureux et que je l’étais encore. Pour que tout soit consommé, pour que je me sente moins seul, il me restait à souhaiter qu’il y ait beaucoup de spectateurs le jour de mon exécution et qu’ils m’accueillent avec des cris de haine.“6

This to me goes beyond understanding. I did, however, discuss the ending of the book with my students at Mamaroneck High School after they had read it, and they had some interesting ideas. But Meursault is certainly the most enigmatic character in any book I have ever read, even more so than Raskolnikov in Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishmen”. I still today don’t understand Meursault’s final words, but they fascinate me.

_______________

And then there was my hero, Bertolt Brecht. In 1966 Allyn and I saw “The Caucasian Chalk Circle”, also at the Vivian Beaumont Theater. It was directed by Jules Irving who had made it into a surrealistic play in which the actors wore masks. It is a play about love and possession and it has a clear Communist message. It is also a story about the fate of a child and for once, in a play by Brecht, it has a happy ending. It was considered the best production by the company during that season. I will come back to Brecht in later chapters, with John in Berlin for example.

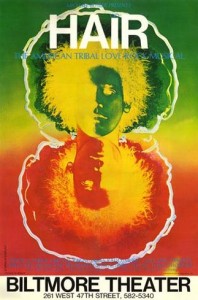

I am leaving out a great number of plays we saw during those years, but there is a superbly important one that has to get special mention. Allyn and I saw “Hair”, a pop/rock show that I would like to call a rock opera.7 It wasn’t really opera though, not any more than “The Threepenny Opera”. Joseph Papp at “The Public Theater” in Greenwich Village produced this exceptional show that had its world premiere in October ’67. It ran for six weeks, then moved to Broadway (after an interim at the Cheetah, a rundown discotheque at 45th Street and Broadway) under the direction of Tom O’Horgan who gave it a major overhaul. At least thirteen new songs were added and Tom O’Horgan put his own imprint on it. It opened at Broadway’s Biltmore Theater in April 1968.

Our dear friends Ted and Norma had seen it at “The Public Theater” and were raving about it. So Allan and I saw it pretty soon after its premiere on Broadway. After all the additions and changes for the better, even Clive Barnes, the famous New York Times theater critic, raved about it with no reservations. It was a hit. It ran for 1750 performances and it made theater history. It played all over the world and Wikipedia says: “‘Hair‘ has been performed in most of the countries of the world. After the Berlin Wall fell, the show traveled for the first time to Poland, Lebanon, the Czech Republic and Sarajevo – American film director Phil Alden Robinson visited that city in 1996 and discovered a production of “Hair“ there in the midst of the war.”

The staging was something I had never seen the equal of and will probably never see again. The stage is bare at the beginning and little by little you see strange creatures creeping-crawling towards the stage from all around it, from up high in the ‘rafters’ and through the audience. They are appearing as if they were outer-space creatures until they all end up on the stage. Now the show can begin. That surrealistic opening I will never forget. And what followed was equally impressive. Most of the songs were so funny and so hippy-clever in their wonderful love of life and the music so catching that I learned the tunes and the lyrics for quite a few of them – without ever trying. It was hilarious and it was immensely clever. This is a hymn to freedom and youth and revolt against puritan mores. And still everybody seemed to love it. Didn’t they see how anti-authority it was? Or didn’t it matter? Do people really yearn to be anti-establishment but don’t dare?

I later saw “Hair” in Paris as well with my sister Gun in the fall of 1970 at the very old “Theatre de la Porte Saint-Martin”, up north of Place du Châtelet. It was great, but it was not like the incredible and wonderful shock you got on Broadway.

____________________

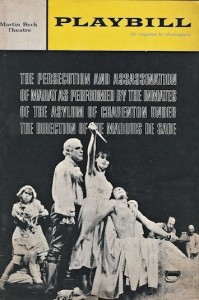

In the spring of 1966 Allyn and I saw Peter Weiss’s “Marat/Sade” – or “The Persecution and Assassination of Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade”. This radical play may well have shocked the audiences in the sixties, but be that as it may, in theater history it began a stage revolution. In New York City, the Royal Shakespeare Company production directed by no other than Peter Brook premiered at the “Martin Beck Theatre” in December 1965. The RSC production first opened at the Aldwych Theatre in London, in August 1964.

Peter Weiss, a Jew, lived in Bremen and Berlin until his family emigrated, first to London in 1934. He himself went to live in Prague to enter the Prague Art Academy, but after the Germans occupied the Sudetenland in 1938, his family moved to Sweden and he himself settled in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1939, where he spent the rest of his life.

“Marat/Sade” is a play-within-the-play, performed at the asylum of Charenton outside of Paris, and it takes place fifteen years after the death of the revolutionary, Jean-Paul Marat, who was killed in his bathtub in 1793 by Charlotte Corday, “a simple Normandy lass” who had fallen in with the political group, les Girondins, and saw Marat as the devil himself. The play is a reenactment of the killing of Marat, who was an extreme radical in the French Revolution. He became a pillar of the group, les Jacobins, which later led to Robespierre and La Terreur, the Reign of Terror.

I remember well the surrealistic/expressionistic stage sets and the costumes that were designed by Weiss’s third Swedish wife, Gunilla Palmstierna. Le Marquis de Sade (here called simply Monsieur de Sade) is the director of the play within the play and to the dismay of Coulmier, the director of the insane asylum, things get quite out of hand at times in the revolutionary fervor of the inmates. “A profound meditation on the nature of revolution, on power and its abuses, means and ends, Marat/Sade is also great theater. (Here is ‘The complete review’ of it.)

Towards the end of 1966 we saw a second play by Peter Weiss, “The Investigation” at the Ambassador Theatre, another remarkable theater production, directed by Ulu Grosbard. This play is Weiss’s ruthless documentary drama of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which he attended, a series of trials running from December 1963 to August 1965. Twenty-two mid-to-lower-level defendants were charged under German criminal law for their roles in the Auschwitz-Birkenau death and concentration camps. Weiss uses actual testimonies of survivors from the camps against their tormentors.”The Investigation” premiered in October 1965 on numerous stages in Germany, East and West, and in a Royal Shakespeare Company production at the Aldwych Theatre in London in November 1965. It opened at the Ambassador Theatre in New York City in October 1966.

Later on, we saw quite a remarkable play by Tom Stoppard in the spring of 1968 – “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead”. It was performed at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre, and was directed by Derek Coldby – an absurdist takeoff on Hamlet, enacted by these two halfwits, who have extremely minor roles in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”.

“The play cleverly re-interprets Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” from the point of view of two minor characters: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The Laurel-and-Hardy-like pair are totally incidental to the action of “Hamlet”, subject to the whims of the King Claudius – who gets them to betray Hamlet…” – “Stoppard’s play turns “Hamlet” on its head by giving these two the main roles and reducing all of Shakespeare’s major characters (including Hamlet) to minor roles.”(Schmoop)

John and I were later to see more Tom Stoppard plays in London and Paris, some very good, others less so.

__________________

Allyn and I started seeing a different kind of theater off-Broadway and we saw quite a few really exciting plays. Plays where you were sometimes sitting more or less literally on the stage. Or the actors walked into the area where we were sitting and there was even some interaction with the audience. This was the height of experimental theater and it was exciting.

I saw, “The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel” by David Rabe, directed by Jeff Bleckner and produced by Joseph Papp at “The Public Theater” in Greenwich Village in 1971. I was back from France, and John was still in Paris, working one more year at Collège de France. I obviously went with a friend, but I can’t remember who that friend might have been. I know I never went alone to a theater in the City.

This play is a protest against the Vietnam War and it is the story about the born loser Pavlo who is emotionally and mentally disturbed. It was succeeded by “Sticks and Bones”, also by David Rabe. I saw this sequel with John in the fall of ’72 at the John Golden Theater on Broadway, and it was also directed by Jeff Bleckner.

This second play is about young David who returns from the war in Vietnam as a blinded vet and how his return from the war creates a family upheaval because of the family members’ lack of understanding of David’s emotional and physical scars from the war. They finally manage to come to terms with both.

Rabe had served in the Vietnam War in a hospital support unit and completed his tour of duty in 1967, when he returned to his university and began the writing on “Sticks and Bones”. It was followed by “Pavlo Hummel” and “Streamers”, a powerful trilogy, as some critics have called it, against the war in Vietnam. ‘The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel‘ was the one play in that trilogy that was produced first at “The Public Theater”.

Back to the spring of 1970. When Allyn and I had already separated I managed to convince him to come with me to see our young friend Tony Schwab from the theater group at Mamaroneck High School. He was in a play “Seven Days of Mourning” at one of the best known off-Broadway theaters, “Circle in the Square” in Bleeker Street. This very Jewish play by Seymour Simckes was a moving story about mourning or not mourning a daughter who had committed suicide. Reason wins out in the end, through the help of a rabbi, and the family learns to overcome religious superstition and mourn the daughter whom they loved. I was thinking about going backstage at the end of the play to say hello to Tony, but didn’t much feel like it since it was a bad time for me.

Tony had been one of our best lead actors at Mamaroneck High School during the years when wonderful Regina Frey taught speech and drama. Allyn and I were Regina’s assistants as our extra-curricular activity. What more could you wish for?

One day as we were working on “The Threepenny Opera” I almost collided with Tony in passing through a door. To my great surprise I sensed electricity in the air as Tony took a step back to let me pass. But it might well have been nothing at all, just Tony being the actor that he was in those days.

There is however a sort of follow-up on this incident. One day some time after I had seen his play at “The Circle in the Square”, I was walking down Mamaroneck Avenue for some reason when I ran into Tony. He suggested we go to a diner just next to where we were for a cup of coffee. We had a very nice chat. Regina was now married and she had left our school, so we were reminiscing about days of yore and theater. I said we had seen “Seven Days of Mourning” and that I’d liked it very much. He said “Why didn’t you come backstage? It would have been very nice talking to you.” I was groping for a reply and I probably came up with some half-truth or maybe even the truth.

I now know (thanks the Internet) that Tony started out as a professional actor, but soon found that it was not really for him. He chose instead to become an intellectual, a writer and a teacher.

A major event in New York City the year John and I spent together before moving to Paris was the superbly wonderful ballet “Petrushka”, which we saw in the fall of 1972 at the City Center, performed by the Joffrey Ballet. I get back to this superb performance in “Chapter 28 (Part 2): Thirteen years in Paris” — Theater and Music. Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” is one of my favorite pieces of music ever. In fact, I would have liked to call my little sailboat Petrushka, but it seemed far too long a word to paint in the stern of my boat, so it got to be Kijé, Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kijé being another major favorite of mine.

Continued: Chapter 18 – Mamaroneck High School and Friends

- A dramatic overview of the black American experience from life aboard 18th-century slave ships to the 20th-century crusade for civil rights. ↩

- The title of the play was derived from the line “Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul” in the poem The Chambered Nautilus by Oliver Wendell Holmes. ↩

- A consortium of civic leaders and others led by, and under the initiative of, John D. Rockefeller III built Lincoln Center as part of the “Lincoln Square Renewal Project” during Robert Moses’s program of urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s. Respected architects were contracted to design the major buildings on the site, and over the next thirty years the previously blighted area around Lincoln Center became a new cultural hub. ↩

- ”Freedom is born from the discovery of the absurd. It allows a person to see everything with new eyes, liberated from habits and prejudice, and to observe lucidly our condition without any hope and without any future. Passion makes it possible to multiply our lucid experiences. … To feel your life, your revolt, your freedom – that is living and living at a maximum (as much as it is possible).” ↩

- “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” ↩

- “I felt that I had been happy and that I was still happy. For everything to be consummated, for me to feel less alone, I had only to wish that there be a large crowd of spectators the day of my execution and that they greet me with cries of hatred.” ↩

- AQUARIUS 2008 Remake – Lyrics by James Rado & Gerome Ragni; Music by Galt MacDermot; Extended lyrics by James Rado; Musical Arrangement by MARTEEN, James Rado, & François Chauvette ↩

How I wish I could have attended some of your classes on anglophone theater. With your vivid descriptions of so many plays you inspire us to delve into these great works of art. It is interesting to note that you have seen adaptations of these plays in Swedish and French, some of which you said were very different from the originals.

I commend you as well on your great expertise and your passion for literature. You are indeed very knowledgeable about theater. I did not know that “Waiting for Godot” by Becket was first written in French and then translated into English by the author.

I totally agree with you concerning “Hair”. I first saw a Swedish adaption in Stockholm that I adored. Then I saw the musical in Paris with Julien Leclerc in the lead and thought once again it was so moving.

Good luck with your last chapters. As usual we look forward to reading them.

Thank you, dear Marianne, for your nice comment. It’s really nice to hear that my meandering thoughts get through to a friend.

Pingback: Sketches from the Life of a Wandering Swede | Siv’s sketches from her life