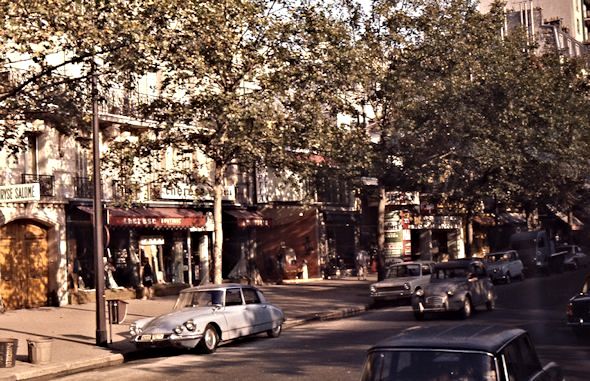

A street on the left bank of Paris, in 1969 – could be Boulevard Raspail. (John’s photo, arriving in Paris)

(Click on the picture to get a larger version)

Henri of Navarre, the Protestant monarch of the kingdom of Navarre which consisted of lands on both sides of the Pyrenees along the Atlantic coast, is known to have said “Paris vaut bien une messe”, “Paris is well worth a mass”. Henri was due to become king of France in 1589 after the death of his childless cousin Henri III. However, since he was a Huguenot and had even fought as one against the royal army, he was obliged to convert to Catholicism. Doing so, he became the first French monarch of the House of Bourbon. He was never fully trusted by either the Protestants or the Catholics, which might be understandable. However, he was a good king and effectively ended the religious wars by signing l’Edit de Nantes in 1598, which assured religious freedom to the French people, including some of John’s ancestors.1

His statue is seen almost as often as the one of Louis XIV. He is often called “le Vert-Galant”, and his statue is on le Pont-Neuf in Paris, at the very tip of l’Ïle de la Cité. The little ‘place‘ halfway across the “New bridge”, which is the oldest bridge in Paris, is called “le Square du Vert-Galant.” The fact that he was indeed a ‘green’ man and a great gallant with the ladies was clearly the origin of his nickname.

I do agree with Henri that Paris is well worth a mass. So here is my mass.

I got to know Paris very gradually, from short visits on my way to other places, when I walked around in the 5th arrondissement, mainly the area of Boulevard Saint-Michel — Boul’mich’ — and Boulevard Saint Germain. In 1954, I was on my way to see my dear friend Gaëtane again, in Luxeuil-les-Bains and, mainly, in Equevilley in the château of les demoiselles d’ Equevilley, her very old great-aunts. (Gaëtane herself would say mes arrière arrière arrière grandes tantes, with some exaggeration.)

Le Pont Saint-Michel going over from l’Île de la Cité to Place Saint-Michel on the West Bank. The plaza is surrounded by buildings with the typical Haussmann roofs.

The edge of Place Saint-Michel is right in the center of the picture on the right, and le Pont Saint-Michel goes across to l’Ile de la Cité. The fashionable buildings right on the Seine have the typical Haussmann look from the renovation of Paris that took place during Napoléon III and the 2nd Empire. That’s when the big boulevards were created.

As I walked along le Boulevard Saint-Michel that first afternoon, I came across a marchand des quatre saisons. Those were mostly elderly men who set up a stand on wheels on a street corner and sold fruits and vegetables of the season to passers-by. I was delighted to find apricots so easily and I bought some and ate them fearlessly without even washing them first. We were not used to fresh apricots in Sweden in those days, and I loved them.

In fact, that year when I came back to Equevilley, Mémé had gone to her savior in heaven and Tata was the still forceful aunt who made us go to church every Sunday and eat the bread, the host, in the basket that was passed around.

But back now to Paris where I found, by luck, an inexpensive little hotel room or rather more a chambre d’hôte in a little street off the Boulevard Saint-Michel. I remember having breakfast, café au lait and fresh bread and butter and confiture, downstairs in what seemed to be the family dining room. A typical continental breakfast.

I also remember buying a baguette, a camembert and a bottle of wine, which was pretty bad and which I also just drank a glass of. That was my lunch in the room. Those marchands des quatre saisons don’t exist any more, and I have no idea why they are gone. With most of the “bouquinistes” who sell second-hand books along the Seine, that is just one more charming feature of old Paris that is no more. All those were such typical sights of old Paris, and it just seems like something is missing in Paris of today. In fact, a lot of old-Paris charm is gone in so many different ways.

However, the daily marchés that border rue de Seine and rue de Buci, off the Boulevard Saint-Germain, still exist and they are wonderful. They are actually sidewalk displays of the stores that are located along those two streets. They were very close to where John had his little apartment in the 6th arrondissement. They sell everything from meat, vegetables,and fish to cheese and pots and pans. The displays are amazing, works of art, especially of fruit and vegetables, and the quality couldn’t be better.

In the fifties and early sixties, and during my following short visits, Paris was a very different world from today. Nowadays the clochards, the homeless, the beggars, are hidden away and lots of those poor people, men and women and children, are fed by organizations like Les Restaurants du Cœur and many others. You used to see, quite often, poor people in rags sleeping on park benches and on sidewalks. There were beggars that remind me of India today, all around the tourist spots in particular.

The French architects who designed Paris in the late 19th century, liked to have open areas, like le Jardin des Tuileries, which is mostly covered in sand and has very little greenery. The same goes for le Jardin du Luxembourg where the sumptuous Palais du Luxembourg, which has been the seat of le Sénat since 1799, soon after the French Revolution, dominates the park from the northern end.

The palace was constructed in the 17th century to be a royal residence commissioned by the queen Marie de Médicis, the second wife of Henri IV and the regent for her young son, the future Louis XIII. The king who had often been the target of assassination attempts, mistrusted by both Protestants and Catholics, was murdered in 1610 by the lunatic Ravaillac.

At la Place de la Concorde is the Luxor Obelisk, which Napoleon did not bring back from Egypt. It was a gift from Egypy to France and it arrived in Paris in 1833 during the reign of Louis-Philippe, who had it placed in the center of Place de la Concorde in 1836.

A lone lady resting in front of le Palais du Luxembourg with gardens. The palace is the seat of the Senate.

The palace avoided destruction in any of the several revolutions that shook the country, a fate that le Palais des Tuileries did not escape. That royal palace was destroyed in the upheaval of the Paris Commune in 1871.

In the vicinity of la Tour Eiffel there were innumerable, mostly African peddlers who would hang on to you if you stopped for a second from curiosity, just the way they do in India and other third world countries. You didn’t see any beggars or junk peddlers in the big fashionable parks, but in areas where there was enough sand — and tourists — there were numerous immigrants selling junk jewelry and leather goods on colorful cloths spread out on the sand in open areas. They were probably all natives of the former French colonies in west Africa.

Les Tuileries and le Jardin du Luxembourg were sacred because middle class and wealthy people were not to be disturbed by hawkers who sell their cheap wares. However, like so many other things in Paris le Jardin des Tuileries has also changed. In the old days you sat down on one of the metal chairs set up around le grand bassin. Right away a woman, called a chaisière, would come up to you and ask for 20 centimes or whatever. No more. The chairs are still there, but no one asks you to pay for sitting down. It was all quiet, rather boring and wonderfully old-Paris. Today children play with colorful rented sailboats or radio-navigated boats skimming across the water. A very different scene from days of yore.

In front of the architectural masterpiece, the cathedral Notre Dame de Paris, cars used to be parked in great numbers. The city decided to change the whole area in front of the cathedral, called le parvis de Notre Dame. They worked on it for years, slowed down by archeological finds that had to be carefully saved, and it finally turned out as something that was more like the way it had once been in the days before the existence of cars – a true and very sizable parvis. That was one of the very positive changes that took place in Paris. Nothing was lost and much was gained.

Alongside the Boulevard Saint-Michel stretching southwards there were stalls for quite a long distance, where people were selling inexpensive leather things from Morocco, purses, wallets and various bric à brac.

There were colorful shawls, cotton shirts and jewelry. Also you could get smoking-hot roasted chestnuts, coconuts cut in wedges and amandes pralinées, burned sugar-coated red almonds that your dentist would tell you never to touch. I loved them.

Most of the historic buildings in Paris are on the Left Bank — le Palais de Luxembourg, le Panthéon where a large number of famous men and women were buried, l’Institut National des Sciences et Arts on the Quai de Conti and of course La Sorbonne and Le Collège de France in rue des Ecoles. Les Invalides, the War History Museum with its famous dome where you will find Napoleon’s tomb, if you are interested in this ruthless warrior, is situated on the Left Bank of the Seine, but farther west, down river. When I was there in 1966 with my group of American young girls there were still war invalids walking around, looking very gloomy and dressed as if this was a hospital. It felt spooky. And of course there is the Tour Eiffel a bit farther down river yet.

Among those honored by the Nation and now lying buried in the Panthéon are Voltaire, Rousseau, Victor Hugo, Émile Zola, Jean Moulin, Marie Curie, just to name a few.

In the 5th and 6th arrondissements, that is le Quartier Latin, which is the part of Paris that I know the best, there were numerous small restaurants, grocery stores and butcher shops. In 1970 I even had a small droguerie, a hardware and kitchen-ware store and also a shoe store in the square, Place Maubert, right next to my street, rue Jean de Beauvais. Alas, those days are gone.

The quartier Saint-Germain-des-Prés in the 6th arrondissement is still today a most remarkable part of the Left Bank. Its history and its wonderful old church, the former Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, dating from 512 AD, the oldest church in Paris, make it a landmark definitely not to be overlooked.

Le Café de Flore just one block west of ‘Les deux magots’, in the heart of Saint-Germain des Prés, 1e 6e arrondissement. Car parked in front of the café is pre-history.

The abbey was ransacked several times by the Vikings but eventually it was rebuilt in 1014 and rededicated in 1163 by Pope Alexander III to Saint Germain of Paris (Wikipedia). Badly destroyed during the French revolution, it got its current appearance after a renovation in the 19th century.

A small village grew up around the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés which was consecrated in 558 by the bishop of Paris. In the Middle Ages, it was outside the city. The town of Saint-Germain in the twelfth century had about 600 inhabitants.

Saint-Germain-des-Prés became a center for intellectuals already in the 17th century, and that is also what we associate today with the names of the famous Café aux Deux Magots and the Café de Flore. A host of intellectuals, philosophers, artists and poets would often be seen in those two cafés. Among them, Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir are the best known perhaps of the so-called “existentialists” who were said to spend most of a day in the back of the café writing while having ordered just one cup of coffee. But there was also Jacqeus Prévert, a poet I love for his compassion and his simple style. And there was also Ernest Hemingway. The list could go on and on with names of more famous people who were seen regularly in this quartier.

John always got meat from his wonderful butcher right on Boulevard Saint-Germain, where he was taught recipes by the butcher. It didn’t matter too much if there was an occasional fly on the displayed meat. It was going to be cooked anyway.

You must not be afraid of germs – suffer from microphobia – if you want to be happy in France. But I do admit that both John and I have suffered from what we call Paris stomach both times we moved to Paris, the second time together in 1973, before we develop natural resistance to the Paris germs. Today of course most meat is behind glass, or pre-packaged in supermarkets.

Those little stores and restaurants are virtually all gone. They have been replaced by chic clothing stores or by other fashionable stores for the young. My little record store close to my studio is no more and, even more importantly, one of our favorite haunts, le Restaurant du Dragon in rue du Dragon close to John’s little apartment, has also been replaced by a clothing store.

As the owner-ladies came towards our table carrying a hot dish, they would always say in a singsong way “Attention, c’est chaud” in their almost inimitable funny way. It has become a standard joke between us to say whenever we carry something hot – or even not so hot. More about le restaurant du Dragon and also about Chez Maître Paul in Chapter 20– My fourth life begins.

It seems unbelievable today, but long before the introduction of the euro, when I lived alone in my little studio in the 5th arrondissement, I remember my sister Gun visiting me in the fall of 1970. One evening we had a delicious dinner on l’Île Saint-Louis and we paid about 30 francs per person for the meal. 30 francs was in fact the standard in those days for a very good meal out, including the wine of course. Later on, when John and I tried out a couple of fashionable restaurants, like Chez Allard, still on the left bank, we did pay more, but no astronomic prices like today. Today 30 € is just enough for a good meal in an average restaurant. Good, but nothing special.

Another one of our favorite restaurants in Paris was la Brasserie Balzar in rue des Ecoles, 5th arrondissement, and it was a bit expensive. We always asked for our favorite waiter, Richard, who later on opened a restaurant of his own. We have been back, but without Richard, it is not the same. (I get back to Balzar in the next chapter, since it was Richard who introduced us to it.) The prices, however, were nothing like Chez Allard, which had a star or two, depending on what year you refer to. A star in le Guide Michelin makes the prices go up right away of course. The era of good food at decent prices is over.

Early evening on Seine; l’Île de la Cité on the left the tower of la Conciergerie in the background with le Pont-Neuf

Homage to Molière, the genius who is still alive

La Comédie-Française was founded by Louis XIV in the 17th century, but it didn’t get its present home in what is called la Salle Richelieu until 1799. It was rebuilt in 1900 after a severe fire. Richelieu who actually governed the country during the childhood and youth of Louis XIV was a lover of the theater and he got the young king to follow in his footsteps. He patronized the actors of the major companies and of course the 17th century was the era of the great French classics. In 1658 Molière and his friends received the protection of “Monsieur”, the title of the King’s brother, in this case Philippe, duc d’Orléans. That’s how Molière managed to go on writing his brilliant plays.

The great Comédie-Française, also sometimes called la Maison de Molière, is an institution that I am extremely attached to. I have a most amazing memory of a 1961 visit to the great national theater. I was stopping a couple of days in Paris on my way to le Midi. One day I decided I wanted to go to La Comédie. When I arrived there was an enormous line of people waiting to get tickets. I didn’t understand what was going on, but I took my place in the line. After a considerable length of time I got up to the guichet. I got my ticket and asked how much it was. The woman said. C’est gratuit. It’s free. I still didn’t understand. It turned out that it was le 14 juillet, la Fête Nationale, and that day those who can’t afford to pay for a seat get in without paying. The salle filled up beginning with the orchestra, which was already full when I got inside. The first balcony came next, from left to right, and up in a spiral. There are four balconies and I was seated in the second, close to the center, a very good seat.

The play was Molière’s ‘Le malade imaginaire’, ‘The Imaginary Invalid’, and the response from the audience was something I had never before seen or heard. People howled with laughter every time Argan had to run to relieve himself after another enema. It was the most fun experience I’d ever had in a theater. Jean-Baptiste Poquelin was the author’s real name, but of course everyone, even in his own days, called him Molière.

Another very different performance was “L’Avare”, “The Miser”, also by Molière. I saw it in 1962, the summer after I’d done my student teaching in Stockholm. It was not done as a comedy, but made Harpagon stand out as a rather tragic and cruel man who sacrificed everything for money. There were not many laughs at this so-called comedy, if any. The mise-en-scène was by Jacques Mauclair, and I believe Georges Chamarat was in the main role as Harpagon.

The funny thing that makes me remember the year of this performance was how, in the intermission, I ran into my major mentor, the French lektor Ström from the lycée in Stockholm where I’d just finished my student teaching six months earlier, the august head of the French department, and his wife, in the grandiose foyer of this majestic old theater.

There have been other funny coincidences in my life, such as meeting a student of mine and her mother from Mamaroneck High School at the Marimekko boutique in Stockholm a few years later during the summer vacation. Those haphazard meetings are hard to believe but they do happen – even though it seems almost unbelievable.

My third visit to la Comédie-Française that stands out in my memory was with Arne in 1969. I had managed to get the whole family together that summer (not to everyone’s happiness though), just because it seemed like a fun idea. Gun and Per had returned home already but Mother and Arne were still around and Arne and I decided to go to La Comédie to see Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand. It was a fine performance, better in the first half than in the second half, which is because of the way Rostand wrote it. It drags a bit from the middle on.

In the last scene Cyrano, the man with the monstrously big nose who has loved Roxane passionately throughout the play, is sitting alone in a garden outside the convent that Roxane has retired to. She has understood that it was not Christian, the young and handsome cadet in Cyrano’s Gascoyne company, that she thought she loved. She had found out that it was Cyrano who had written all those beautiful letters to her every day, signing them Christian and she now knew that it was Cyrano she loved. On the stage the autumn leaves were made to fall down slowly and continually. The audience was getting a bit bored during the last act, but then suddenly a big plane tree leaf landed on Cyrano’s head, without his knowing it of course. The audience started snickering, and from then on the interest in the play seemed to be revived.

The dueling scene where Cyrano is reciting a poem while he is dueling is my favorite scene in the play. I remember reading the play when I was with Gaëtane in Ecquevilley in 1954, and I liked it then too.

The outstanding actor, Gérard Depardieu, played Cyrano de Bergerac in the movie from 1990 and he was magnificent. He is not a handsome man, but they still had to add quite a bit to his nose to make him be a real Cyrano.

In the spring of 1971, John and I saw Le Misanthrope at the Théâtre de l’Odéon in the mise-en-scène by Antoine Bourseiller, a magnificent performance. I believe it is my favorite among all Molière’s witty plays that put down hypocrisy and general stupidity. It’s amazing how a writer who lived and died in the 17th century can be so much alive and speak to us in a way that has become anything but moldy by the 250 years that have gone by since this genius wrote the play.

It was also a tour de force by Bourseiller whose staging was so lively and authentic that, if it hadn’t been for the costumes, it could have been written yesterday. I remember vividly how, for one thing Bourseiller had actors move around and converse in the background, while the action was taking place in the foreground. Fortunately he hadn’t fallen into the silly trap of so many directors today who dress the characters up in modern costumes. A sure way of losing the authenticity of the play, be it opera or classic theater.

Arne and I, on one of our many walks through Paris at the time when we lived in the 13ème arrondissement, one day decided to go to the museum at the back of the Opéra de Paris. Arne had the brilliant idea of going to see the collections that are housed in the back stage areas of the huge building.2 There are old costumes, old instruments, old manuscripts. It’s a most interesting museum that few people know about.

Arne was such a good walker that even in the late 70s I could sometimes barely keep up with him on our strolls through the big city.

Continued: Chapter 20 – My fourth life begins

- Unfortunately the Edit de Nantes was revoked by Louis XIV in 1685 ↩

- La Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra; Archives, bibliothèque et musée ↩

The first photo looks like the Paris of my dreams (I’ve never been there). And despite the fact I come from staid old Toronto, the descriptions of the street scenes and vendors is exactly what I remember from my youth (my area was full of immigrants from Europe! particularly Italy). I miss all of that immensely. Very evocative story telling, Siv!

The bit about Paris stomach reminded me of my second trip to Venezuela. Debbie bought some cookies from a street vendor the evening before we were to leave for home. Never gave any thought to the flies.

She was tremendously ill during our six hour flight and we ended up at the hospital once we were home. She was put on an IV drip and given a lot of antibiotics. And then the public health people showed up and quarantined her for two weeks. It turned out to be shigelosis and even though I’ve been back to Venezuela since, she won’t.

What wonderful descriptions of Paris some forty years ago! Yes, things have definitely changed. Today numerous people seem to suffer from microphobia, whereas before we were not obsessed by hygiene. Your account is so rich with interesting historical facts, and I love the way you describe theater performances you have seen like the plays by Molière — it truly brings them to life. It’s a pity so many of our favorite restaurants have turned into clothing stores. What will the future bring? Anyway, congrats on all this good work.

Marianne

Pingback: Sketches from the Life of a Wandering Swede | Siv’s sketches from her life