I am starting my second life – an ode to my dearest friend Gaëtane

The father of the family, Monsieur Spach, came to Basel to pick us up in his cabriolet car, and I’ll never forget the honking in every curve on the small road going west to Luxeuil or Thierry’s non-stop chatting. He had to tell his dad about everything that he’d seen and done in Sweden with his stepmother, Ulla and her younger sister. All I understood was that the replies from his dad were, almost unchangingly: Oh là là!!! My first French lesson in the country. I didn’t understand a thing of Thierry’s chatting.

We arrived at a nice big house in a little street that curved off from the main street. There used to be two factory buildings down a little hill behind the house, but only one was now in use. Shoelaces were produced and, unfortunately, the market for such things was very slow.

The little town of Luxeuil-les-Bains had just one main street. About a hundred meters from our house was the most extraordinary invention I didn’t even know existed anywhere in the world – les lavoirs, in a street appropriately named la rue des Lavoirs. Coming down our street, rue Henry Guy, to the main street, we passed les lavoirs where women in black – always dressed in black – were kneeling, scrubbing and rinsing their laundry in the water from the little stream that ran by the wooden construction that was les lavoirs. It was to me an unknown world. It seemed as if I was going back a century in time.

Marie, la bonne, lived in that street in a very modest old building and I was once invited to come in and see her home. There was not one single armchair. A big table in the middle of the room, which clearly was an all-purpose room, and straight-backed chairs. But the thought passed through my head that even if you had given her and her husband an armchair or two, they wouldn’t have felt comfortable in them.

I have since learned that in the homes of small farmers, there is one big tabel surrounded by quite a few straight-backed chairs — and in later days a television set — and that is where the family lives and receives occasional visitors who are offered a glass of pastis, be it Pernod or Ricard. This room is the kitchen and the only living area in the house.

Back to Luxeuil now. My almost seven months in Luxeuil with the Spach family turned out to be for better and for worse. The young Swedish wife, 7 years my elder, did not like to cook. She left it all to me, which was a lot of responsibility for a 19-year-old who had never done anything but study and give a helping hand in the kitchen. I had very rudimentary notions of what cooking was all about. We could all cook scrambled eggs in my family, but Gun insisted on having canned sardines to go with the eggs.

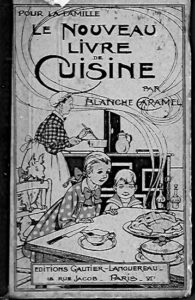

There was the funniest old cookbook I have ever seen and it was my only guide to what I prepared. I think it was Gaëtane who taught me how to make salad dressing, and I still use just about the same recipe.

The young wife, Ulla, (Madame Spach to me) showed me this well-used, yellowed book that was titled La nouvelle cuisine française by Blanche Caramel. It looked a hundred years old. And for the rest it was simply ‘Débrouillez-vous!’ (Just do it!)

The name of the cookbook, and in particular of its author, was hilarious, but it taught me how to make a very tasty blanquette de veau, among other things. Choucroute (Sauerkraut) I made according to Ulla’s instruction and, surprisingly enough, it was good.

What saved me was that I did not have to prepare breakfast, since I hate to get up early in the morning, and especially to work for a family. I didn’t quite know why I owed them all the work I did. I cooked two meals a day, but breakfast, le petit déjeuner, was fortunately prepared by Marie who came in half days and did the rough work.

So the great relief was not to have to worry about breakfast, and everybody came down at his or her suitable time. I remember having my breakfast alone, after the “kids” had gone off to school. It’s clear though that I was made to work far more than it had been agreed on. Ulla did not want to be the housekeeper, so I became the one who had to take care of all the things Marie didn’t do. Ulla was in fact her husband’s secretary and/or accountant in his office premises that took up a large part of our house on the ground floor.

I took the work in my stride, even thoug Ulla treated me condescendingly; clearly afraid that I might feel superior in some way since I had a ‘real’ studentexamen (baccalauréat) and she had, as whe told me in Sweden when we met, ‘just’ a commercial studentexamen, as she self-consciously told me at that time.

I liked to do the shopping though, especially le marché, which was something all new to me. The salespeople would wrap up what they sold in newspaper, or in fact most often they just poured the vegetables or whatever straight into your bags. Meat was at the butcher’s store in la rue des Lavoirs, and it was not bad quality. Even simple biftek was quite good.

I thoroughly enjoyed my long walks in the neighborhood, to the village south of Luxeuil, Saint-Sauveur, and into the forest and its Roman road. This was a thrill for a young Swede, who had never seen anything like it, even though there wasn’t much to be seen. Just knowing that this was a road, with big flat stone slabs where the Romans had driven their chariots, was amazing to me.

What struck me the most though on my walks on a sunny day was the way elderly women, all dressed in black, would move a chair out in front of their little house and were just sitting looking happily on whatever went by – which was not very much. A different world.

________________

I got along very well with everybody in the family, except with the lady of the house, who to me was not Ulla, but Madame. My very good relations with the three children, of whom Gaëtane was hardly a child any more at the age of 17, would certainly not have made Ulla like me any better. Ulla knew for sure that Gaëtane would not have anything good to tell me about her stepmother, who was just 26 at the time And: who had been the gouvernante in the house the previous year.

Gaëtane was actually supposed to have left home to go to her very high-class boarding school, Chambord, from previous years, but her father realized that it would be too costly and plans were changed. Fortunately for me.

Gaëtane was two years my junior, but if anything she was more of a woman than I was. It was Gaëtane who did the most to improve my French. I still remember today words and phrases that she taught me. ‘Muguet ’ I said once with a question mark. And Gaëtane quickly answered ‘Oh you know, the flower your mother likes so much.’

She remembered too. She would say when telling me about a surprising thing ‘Tu te rends compte!’ And Monsieur Spach would say ‘Vous vous rendez compte!’ in similar contexts. So soon it occurred to me that they were saying THE SAME THING. Se rendre compte – of course!!!

Thierry was a clown and he got along with everybody. In fact, he still today has very good relations with Ulla and her two children whom he considers his brother and sister. But he does say that Ulla is very difficult to get along with. Dominique, the girl, was born when I was there, was a chubby little child when I came back a year later to visit, and I remember Gaëtane holding her in her arms. Thierry tells me that she has remained chubby.

Marie, the daily maid, was a sturdy woman always dressed in black too, who was far from stupid and did a good job. Once when I was washing a salad for lunch in the basement kitchen (there was a small kitchen next to the dining room as well), Thierry was standing next to me and he caught me about to throw away the small center of the salad. He said ‘Mais vous ne jetez pas le cœur!’ – ‘Si’, I said, ‘pourquoi pas?’ – ‘Mais je mange le cœur, moi’, he said. Marie had overheard us and she said very fast: ‘Pas le cœur de Mademoiselle, j’espère’. I have told Thierry about this little episode and how I thought Marie was quite smart. But he doesn’t vouvoyer me any more.

However, I was still like a member of the family, liked or not liked by Ulla, and very soon Gaëtane and I became close friends. The two younger children were Marie-France, 13, and Thierry, 12. The second son, Alain, 15, was staying with his mother at the time. Marie-France was a quiet girl with beautiful dark eyes. When I asked Thierry how she was doing now, he said ‘She still has her beautiful eyes.’ She married an artist and soemhow she was the one who took over the château of the two old aunts from their mother’s side, known only by the names Mémé and Tata. Thierry could hardly believe it when I started talking about them quite a few years ago. He said “I feel as if time is standing still.”

________________

It got to be seven months of work but also lots of fun and partying, “surprise-parties” (a term that has been long gone), most often at our house, but also at the homes of the other girls. Our boyfriends were barely allowed to leave their houses for the Saturday evening parties.

Once when we had planned with our boyfriends to go to the movies together, Gaëtane and I were a bit put off when they arrived with their fathers. That was the small town in old France!

We were often at the home of the twins Weber, the most different twins I’ve ever known, one tall and slim, the other one short and chubby. One of them was called Marie-Claire but I don’t remember which one. Their father was the Directeur de l’établissement thermal, which served us well in the early spring when he had the pool heated for us alone, before the season started. We went swimming in March when it suddenly got warm after a very cold winter.

There was still a pile of icy and dirty snow outside the wall of our house, but next to the swimming-pool the violets were blooming. I was lying on the sloping lawn by the pool next to my boyfriend Michel, looking at the violets and feeling that life was good. I was to leave to go back home very soon.

Gaëtane’s father was very liberal and he let us buy a few bottles of Vouvray mousseux for our parties. He said champagne, non, but we could have the best mousseux wine there is. We would bake a cake to go with the wine and that was enough for a good evening.

After our parties, when people were asleep in the town, we would walk through the town, arm-in-arm (bras dessus, bras dessous) across the whole street down the center of Luxeuil, singing à tue-tête silly songs such as :

Et Joséphine elle est malade, elle est malade, malade d’amour

Pour la guérir il faut de la tisane, de la tisane, carottes épinard et poirots poirots poirots

Viva les pommes de terre, viva les pommes de terre, carottes, carottes, carottes, épinards et poirots poirots poirots

The people asleep in their beds, or trying to sleep, were not happy and they did let us know it, but we couldn’t be toned down.

Monsieur Spach’s mother was une grande dame with a big heart. It was obvious that the family had seen days when they were in a way the aristocracy of the town. When I was very sick in the Asiatic flue that fall, Grand-mère was the one who came over and took care of me. With very simple means, but it worked. Gaëtane and Thierry came and chatted with me every day.

Also, when Monsieur Spach was upset and banned parties for some time because he had seen Gaëtane sitting on her boyfriend’s lap at one of our parties, Grand-mère lent us her apartment. We had to take down her velvet curtains so they wouldn’t smell of smoke afterwards, but that was all right. People smoked in those days. But we were young and strong and everything like that was just fun for us.

And there was ‘The Day the Cat Ate the Cake’. It was the evening before Monsieur Spach’s birthday and of course Gaëtane and I were going to make a cake for him. Said and done. We were in the downstairs kitchen where the cat and the cute white little dog, suitably named Blackie, were allowed in. We happily put the cake together and after it was baked in the oven, we put it on the stove to cool off before putting cream on it. Suddenly, turning around from the pantry we saw the cat up on the stove and he had already gobbled up a considerable piece of the cake. We scratched our heads and considered. There was only one thing to do. We baked another small piece of cake and once it was done, we made some glue with gelatin and stuck it on to the main cake. It looked acceptable and wouldn’t show under the cream. We laughed all the way through the event and finally, when the deed was done, we laughed even more and I said ‘On a racommodé un gâteau’ (comme on racommode des chaussettes). Gaëtane added ‘avec de la colle de poisson’. I didn’t know at the time that gelatin was fish glue, but I know now. The next day everyone ate it with a good appetite and we never told anyone that the cat had eaten a good piece of the cake. Oh, there was a candle in the middle of the cake too of course and Monsieur Spach was very pleased.

Gaëtane was a pretty young woman full of charm and joie de vivre. She had fun ideas, she was smart, she had a ringing, happy laugh and she had many talents. When I think back on what she did with her life it feels like such a waste of charm and possibilities. I lost touch with her early on, but through Thierry I know that her life ended very sadly. I miss her. I would have so much to talk to her about. I miss her very much.

_______________

It was really thanks to Gaëtane that this got to be – as I figured out much much later – my second adolescence, my French adolescence. I was a late bloomer and the fact that my boyfriend, Michel, was a couple of years younger than I did not bother me, or him, a bit. I have ever after felt completely at home in France. My Frenchness had been made and it remained with me. I was now at home in two countries. However, it wasn’t until my return to Luxeuil and to France the following year that I got to know Paris too.

On the very last day of 1952, Gaëtane and I managed to tune in Swedish radio on New Year’s Eve and there was a recorded version of Anders de Wahl, one of the most historical Swedish actors ever, of his late 1940 reading of “Ring, klocka, rin” for the Swedish nation, the same way we had heard him readin it every New Year”s Eve for as far back as I could remember. I almost felt transported to Sweden for a few moments.

Ring, klocka, ring i bistra nyårsnatten

mot rymdens norrskenssky och markens snö;

det gamla året lägger sig att dö . . .

Ring själaringning över land och vatten!

(Original by Alfred Tennyson – Ring Out Wild Bells, but an excellent translation of a poet I have never thought much of – translation by Edvard Fredin)

And then came all the bells ringing from innumerable churches all over Sweden, most likely beginning with the bells from Uppsala Cathedral..I didn’t feel completely abandoned by my own country and family when I heard the Swedish language on the radio and the beautiful sound of all the various church bells.

On Christmas Eve, Gaëtane and I went to the church for Midnight Mass just to hear the choir sing. It was exactly what I needed to feel that there had after all been a Christmas.

A rather sizeable sum of money came down to the Spach family like manna from heaven just before Christmas and that’s how we bought a huge bloc de foie gras – there were six of us – and this first foie gras in my life lasted for many days. I loved it. A goose stuffed with chestnuts (purée de marrons) was cooked instead of a turkey for Christmas Day and that time I was not the cook. When something very special was to be made, it was Monsieur Spach who did it, this time assisted by Ulla for the stuffing. I copied a couple of his gourmet dishes later in Sweden and they came out quite well.

Whenever Monsieur Spach saw a good reason to have an apéritif, he would get the bottle of Noilly Prat sec out from behind the bar in the dining room, and I believe that it was only he, Ulla and I who were included in this exclusive little ceremony. Gaëtane was still considered too young apparently. That is the brand of vermouth that I have always bought ever since then. In the very French way, no hard liquor was ever even thought of.

Gaëtane and I used to play Monsieur Spach’s good supply of classical records, 78s of course, in the evenings when everyone else had moved upstairs. It reminded me very much of home. Gaëtane did not take her homework very seriously and in fact she had never gotten used to hard work at all. I rarely saw her work. Maybe that became her downfall. Do I sound like the Protestant we were brought up to be in my country? I do remember though helping her with her German homework on a couple of occasions. She simply expected me to know everything she had to know. I had passed studentexmen – le baccalauréat – and so I was supposed to know.

Another old world opened up to me that year, all new to me. Gaëtane had in fact been brought up her mother’s two old aunts. There were two aunts, whom Gaëtane explained to me were her great-great-great aunts (arrière arrière grandes tantes), called just Mémé and Tata by the children. In fact, they were les demoiselles d’Equevilley. They were on her mother’s side – and VERY Catholic. Gaëtane told me I could not let them know I was a Protestant (in fact I was nothing at all – religion- wise). I had to tell them I was a Catholic. Tata said suspiciously “But Sweden is a Protestant country.” “Yes,” I said, “but there are Catholics too”. (Oh, the horrible lie – It was extremely hard for me to lie and especially about religion, for some reason.) I had a friend who was a Catholic, so I thought it sounded plausible. I just had to lie in order to be accepted by the old ladies.

Tata, who has long been dead by now of course, will always remain with me as the old lady who would vouvoyer her cat. When she got annoyed by the cat running around her feet in the kitchen, she would say Allez-vous-en! Allez ouste!

It was in fact Tata who had been responsible for Gaëtane’s education, in all subjects except math. So she had to take the bus to Vesoul, the closest town, to see a math tutor. No wonder she had a bit of a problem with German, and with school in general. I didn’t know this at the time. She kept this a secret from me, but Thierry told me about it much later one day twhen we met for a long chat over lunch in Vieux Lyon and then walking around because there was so much to talk about. All I knew about Gaëtane’s schooling was Chambord, the very exclusive boarding school in la vallée de la Loire where she spent a couple of years among the very upper-class and high nobility children who went to that school.

We often took the bus from Luxeuil to the château in Equevilley on a Sunday, and the first thing we had to do was go to church, la Grande Messe. We had to take that little piece of bread that was passed around in a bread basket. Mémé who was tall and skinny was too feeble to go to church so Tata, who was shorter and stocky, brought a piece of “blessed” bread back home to her sister and Mémé crossed herself and ate it devoutly. Oh, religion!

Sometimes on our way to Equevilley, Gaëtane and I would sit in the back of the bus and sing loudly – à tue-tête – the little pieces of songs we knew. People in the bus would turn around and smile, visibly amused. This was France, not stodgy Sweden.

On a chanté les Parisiennes,

Leurs petits nez et leurs chapeaux

…

On oublie tou-out

Sous le beau ciel de Mexico

On devient fou,

Au son des rythmes tropicaux

Yves Montand, Henri Salvador, Charles Trenet, Serge Reggianni – we listened to them all and sang loudly and with great gusto the little we knew of the lyrics of their songs, at home and in the bus or wherever we happened to be. Gaëtane was probably the most fun young girl I’ve ever known.

Oh, les beaux jours, et les jours durs aussi…

J’aime flâner sur les grands boulevards

‘y a tant de choses et tant de choses et tant de choses à voir…

My favorite, Yves Montand, singing ut with his usual bravura.

And, above all maybe, ‘Les feuilles mortes’ de Jacques Prévert.

C’est une chanson

Qui nous ressemble

Toi tu m’aimais

Et je t’aimais

…

Mais la vie sépare

Ceux qui s’aiment

Tout doucement

Sans faire de bruit

Et la mer efface sur le sable

Les pas des amants désunis

Oh, the crooners. I never liked the American crooners, but I loved the French ones. I can still hear Yves Montand singing ‘Les feuilles mortes’. And the immortal Edith Piaf, the French legend, nicknamed the little sparrow (le petit moineau or Môme Piaf), because of her tiny stature. Yes, her big breakthrough had already come with ‘La vie en rose’ several years before my time in Luxeuil, a song that most people loved so much, but I didn’t.

Much later I did get to like Piaf. I remember Milord which I bought as a 45 rpm. Once in Paris on my way back from le Midi, I went into a record store (Remember the days of small record stores, where you got excellent advice from the owner?) on Boul’miche to buy La Foule by Edith Piaf. The store owner handed me the little 45 rpm record and said ‘Mais attention, c’est vieux.’ I said ‘Oui oui, je sais, mais ça ne fait rien.’ For those who don’t like Piaf I can only say that they might find her a bit overly emotional and too loud, somewhat like Liza Minelli, in terms of loudness. But one thing you can never deny is her passion. Wow, the passion coming out of her voice and her appearance is breathtaking. I don’t think I would like Milord any more. It’s just too much. But La Foule still moves me. Particularly against the background of her tempestuous life. And if you have heard her singing ‘Padam… padam… padam…’ once only, you will never forget it again.

She was still around in the late fifties although very sick. I remember well her marrying her third or fourth husband who was twenty years her junior shortly before her death in 1963. She was only 48, but she already looked old, certainly because of her morphine and alcohol problems.

A fond and fun memory was my boyfriend Michel coming by our house, standing below my window, whistling Tango bleu. It was the signal for me to come down and go for a walk and a bit of loving. I heard his whistling and I threw on a coat and ran downstairs. Happy days. Yes, and hard days too, but that is now forgotten. This was indeed my French youth, and my introduction to France could hardly have been less touristy.

Oh yes, and Michel looked a bit like Serge Reggianni, the actor and singer from those days.

Continued: Chapter 5 (Part 3) — One year after