Chapter 23 – Back to Paris

Jacques’ question to John changed the world. We saw the blue sky and the birds were singing again.

I had a problem with my divorce from Allyn, but now time was running out for our living in the United States. It had dragged out for various reasons and when it was supposed to be all done and finished, the papers were mysteriously lost at White Plains court house.

Finally, in desperation – we were supposed to get married in two days – we went to White Plains to find the blooming papers. The man who was in charge of my case said “No, they had not turned up”’ As we were leaving, very distraught, he called over to a colleague down the hall “Have you by any chance seen the divorce papers for Mrs Siv Phillips?” The man said “I see, those are the papers — I had no idea where they belonged.” Oh, bureaucratic efficiency! We left White Plains with light hearts. We already had reserved a time with the mayor of New Rochelle. John had told his parents that we were coming down on such and such a day, but he wasn’t absolutely sure we would be married.

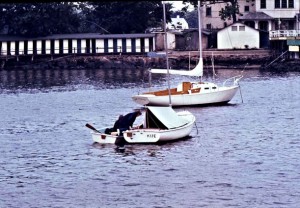

The morning of our wedding arrived. It so happened that I had sold my dear sailboat, Kijé, at the price I had asked for, which was fair in my case. I had bought a new tarpaulin after a violent storm tore the original one apart. A lot of the boats in the harbor were more or less damaged after that wicked storm. I had bought a cradle for the wintertime, which was a must, and I had also bought my little dinghy. I had convinced the man on the phone that my price was perfectly sound. He had finally accepted it. So I now wanted my little Rhodes 19 to be clean and I knew the deck was not. Early in the morning I put on work clothes and rowed my dinghy out to my boat which was anchored in the middle of the little bay of the marina. As I was rowing all alone in the harbor, the world around me seeming deserted and bewitched, I was in great spirits and I sang loudly all over the marina.

I’m getting married in the morning,

Ding-dong the bells are going to chime,

Pull out the stopper, Let’s have a whopper,

But get me to the church on time.’

I have always loved “My Fair Lady”’ and Eliza’s father, Doolittle, is one of the most fun characters both in Bernard Shaw’s play, “Pygmalion” and in the musical. Even though the lyrics didn’t fit in too well with the situation, I had the time of my life, rowing out to my little Kijé, belting out Doolittle’s song for all the world to hear. I climbed on-board, cleaned off the deck, put the tarpaulin back on and got back to Harbour House as it was called, with British spelling, if you please!

When I arrived, John was a bit panicky but I knew what I was going to wear and there was no problem. In no time I was wearing my Yves Saint-Laurent suit, not even new for the occasion, skirt, not pants, nice shoes, and we arrived at the City Hall in good time. We had no witnesses, so two secretaries were called in to certify our marriage, our signatures, or whatever. But the most lasting memory of the ceremony was looking over the head of the Mayor at a photo where he was shaking hands with President Nixon. We managed to keep straight faces anyway.

As we arrived in Orlando that same evening, my parents-in-law were at the airport to meet us, as usual. John pushed me up front a bit and said to his parents “Meet my wife.” Everybody laughed. I had known them for almost two years. But they were not sure that my divorce papers had finally been found and that we were actually married.

___________________

This was in the spring of 1973 and the move would take place as soon as the spring term was over. There was a bit of a problem for me, having to give up a secure tenured job, and well paid at that, having no idea what I might be able to find in Paris. My dear friend Janet Rogowsky tried to tell me I should stay one tenth year in the U.S. so I wouldn’t have to give up my retirement pension — ten years work was a minimum — but there was no way I was going to stay on alone and let John move to Paris without me. Money be damned.

Exit with a bang and much laughter

My young friends Nora and Rita had offered to help us with the packing. We thought it would be great if they would help us with our several hundreds of books. Their eager and smiling faces helped us a lot through the drab job of preparing for the move.

What most stands out in my mind after that was the very last day. The apartment was practically empty and we were packing our trunks and suitcases. John had the bright idea that we were going to celebrate our move back to France with a glass of Aalborg, that is ‘snaps’ in Swedish. But Aalborg is Danish snaps. But we were busy and in different rooms of the apartment, so we yelled Skål from a distance to each other and merrily went on with the very last part of our packing. Maybe the one glass got to be two glasses, since I remember getting quite giggly.

However, we got the last trunk closed after picking Mélisande out of it. Actually, that was while there was still some room left in it. She had got ensconced in a trunk to make perfectly sure she was not going to be left behind. Cats do have a strange sixth sense about packing. They know perfectly well that something drastic is happening and that it’s a matter of getting in on the trip.

We also sneaked out of paying the extra month’s rent that the landlady had requested. I had apparently given notice a bit too late and she claimed I owed her the next month’s rent. Ha ha! — I had even paid a month in advance when I first rented the apartment. So forget it! Somehow, I will never understand how she caught up with us in Paris and threatened legal action. I replied “Good, lady, go ahead and sue me”. I never heard from her again. She would have the apartment repainted and rented out before the end of the month of July, so I had no guilt feelings for the poor landlady and her shenanigans. We were burning our bridges.

The taxi that was going to take us to Kennedy Airport had arrived. We put Mélisande in her cage on a bunch of newspapers, the cage on John’s lap, and off we went. It’s a long way from New Rochelle to Kennedy Airport. We traveled through Co-op City, the newly built-up areas before you get to cross over to Queens and Long Island on Throgs Neck Bridge. Co-op City didn’t even exist when Allyn and I first arrived north of that area. It’s now like a city in itself, ugly high-rises, but hopefully it won’t become a slum in no time since there are no greedy landlords.

This was when it happened. We had just crossed the bridge when a powerful odor was spreading through the back of the car. This was a first. Mélisande had always been an excellent traveler but this time it had been too nerve-racking for her. Worrying about possibly being left behind, which had actually happened when we went down to Orlando for our brief honeymoon in Sarasota on the west coast of Florida. But that was the only place where we didn’t bring her along. When we traveled by car to visit with our friends Jim and Sandy, then living in a suburb of Philadelphia, Mélisande was always with us.

Be that as it may, something had made things be too much for poor Mélisande and we smelled the effect of it. John looked at me for agreement in what he was about to do. I knew and I nodded in silent understanding of the weight of the act. Okay, John lifted her majesty, folded up the newspapers and put her majesty back down. He opened the window with a questioning look at me again. I nodded once more. We were then driving through some fairly uninhabited areas and, to our great relief and eternal shame, we polluted the environment with our precious kitty’s left-overs. And we chuckled happily. The trip back to Paris had started well.

______________________

The rest of the moving went smoothly and we were suddenly settled in a nice apartment building in one of the most charming old quartiers in Paris, la Butte aux Cailles in the 13ème arrondissement.

Our wonderful friends Jacques and his wife, Mimi, generously lent us their apartment in the same arrondissement, close to where we were going to find our first home. All went well, except for a little shock we had a couple of days before we were about to give the apartment back to our friends. We found that one of the mustard yellow plush armchairs in the living room was fairly hopping with fleas. How on earth Mélisande had managed to get infested with fleas, we will never know, but there we were. John bought a disinfectant spray (une bombe as they call it here) and we did a thorough job killing fleas both on Mélisande and on the chair. We seem to have managed. Anyway, we never heard anything about it and Mimi was the most perfectionist housewife we’ve ever known.

Very young Puppy, who never got another name, in Siv’s arms, as we are getting ready to leave Monsieur Rothling who was the breeder.

We found an apartment that was just what we wanted, but our furniture took a long time arriving from New York. So in the meantime we bought new beds and a couple of deckchairs for the living room. It looked funny but with our 3-month old German shepherd puppy it looked adorable to us. I insisted on a German shepherd since I still had Sappo, the wonder dog from my youth, in my mind.

I admit that it was a bit loony to have a big dog in an apartment in Paris, but a big dog was what I wanted. I always took good care of him, walked him daily and threw sticks for him in the few places that were available for that sort of romping around.

But there would be La Fontaine a year later and Puppy had the time of his life there, and so did Mélisande, of course.

La Butte aux Cailles (the quail hill) is anything but a posh area, but so much the better. It had the ambiance of an old French little town and our five-story apartment building really stood out among the old buildings around us as the only modern one, even though it was of the same height as the surrounding buildings.

Little neighborhood stores were all around us. We had our fish market, our butcher, our “triperie” (triperie = innards butcher). There are the ordinary bouchers in France, les charcutiers for prepared foods, pâtés, salades, different kinds of ham, etc. and also tripiers for those who like innards, which we do, sweetbreads, calf’s liver and kidneys. John also likes andouillettes, which is tripe sausage, therefore “triperie”.

The only picture we have of our first apartment building, 4, rue Jean-Marie Jégo. Ready for a trip in our Peugeot 204 to our ‘fermette’ in l’Indre.

And there was our little old-fashioned grocery store, a family business, where they even sold excellent wines — just around the corner.

Our fish monger is a story in herself. Dear old Jeannette will be history, or probably already is, at least in the 13ème arrondissement. Her store was in rue Bobillot just where the rue de la Butte aux Cailles turns off and Bobillot goes on down to rue de Tolbiac, close to where Jacques and Mimi lived. The display of fish was on tables set up every day on the sidewalk, as is the custom in food shopping quartiers. The business was done on the sidewalk. Jeannette was a character. With her husky voice and her no-nonsense behavior, a friendly smile on her lined face and a fairly dirty plastic apron over her white fishmonger’s smock, she charmed her customers from near and far. She was always chatty and smiling even though she must have been in pain from a hip problem that gave her a pretty bad limp. She rattled off simple and good recipes, a French habit, and from her we learned a basic recipe for oven baking several kinds of fish: olive oil, white wine, salt and pepper, slices of onions and tomatoes. Half an hour in medium hot oven.

She eventually got surgery for her hip problem and came back more smiling than ever, and no more limping. Business was good and she opened a reastaurant right above the store. What was it called? “Ches Jeannette” of course. After we had left la Butte aux cailles, she moved her business to a new location in the rue de Tolbiac. Her success was in steady increase. Our friend Jacques who lived nearby was one of her faithful customers. One day when a man offered to serve him, he said, in his own brusque but humorous way: “Qu’est-ce que j’ai à faire à un grand moustachu. Je veux Jeannette moi, et pas n’importe quel gaillard.”

And let’s not forget the street itself, la rue de la Butte aux Cailles and the entire quartier, which is (or was) probably unique in its kind for Paris. It seemed as if it hadn’t changed in the last one hundred years and there were a few inexpensive little restaurants with tables taking up all of the sidewalk. They served food you didn’t even see on the menus in fashionable restaurants. But it was good and cheap and the restaurants had a homey ambiance that you rarely found even back in those days. There were old apartment buildings and quaint little shops, such as a quincaillerie, hardware store, the kind of store that is becoming an increasingly rare sight since those days in the 1970s.

Elderly people who had never lived anywhere else — or even been anywhere else — were seen walking around on the street where one sidewalk was mostly taken up by the restaurants during the mild seasons. There was very little traffic in the street, so we were all safe walking on the kind of cobblestone paving in the street. This quartier is, or was at least, a microcosm where the elserly inhabitants probably didn’t even know any other parts of the big city. To these people from another era, the 16th arrondisement would be like another planet.

The next street, after ours, that went off the rue de la Butte aux cailles — rue Samson, was a street where a lot of “artisans” had their little shops. There were, among many others, the menuisier (cabinet maker) who repaired wonderfully well a bottom drawer of my dresser that young Puppy had chewed on when I was at work. And there was the seamstress who made the cushions for two rattan chairs that we bought before our furniture came over from New York — the cushions came a bit later but we still have those chairs, and cushions too.

In our own street, Jean-Marie Jégo, we would often see about dinner-time a little womn about 60 or 70 years old come out in front of her building with her salad basket which she swung vigorously back and forth on the sidewalk. You did not spin the salad in the old days — swinging it was the way you did it.

I also emember seeing a little old lady moving a chair out on the sidewalk in our own street. She had probably known this quartier when there were chickens running around in the backyards, when it was still a village in the big city. There must have been many of those little islands in the big city back before World War II at least, since you still saw traces of them in the seventies. But la Butte aux Cailles was very special, and it might well have been the only one that had survived.

Paris, like New York City, is not one world. It’s a mixture of widely different worlds.

This woman had most likely lived in the same place since the early years of the 19 hundreds and though she must know that the world had changed she was not about to change her habits. I also saw her, or some other elderly woman, put a kitchen chair out on the sidewalk on a sunny day and just sit there and watch the passers-by. There were not many of those in our street, but she had her bit of sun. And she was not dressed in black like the women in Saint-Sauveur, the little village close to Luxeuil-les-Bains, which I mentioned in another chapter.

I see from Google Earth that this entire quartier has been gentrified and there may not be any old-time ladies walking in the street today. The cobblestone-like paving has been replaced by new and perfectly flat paving stones, geometrically arranged, but definitely no asphalt. The “spirit” of the quartier has been preserved, as far as it was possible. But you may not eat rabbit any more in the up-scaled restaurants. All façades seem to have been painted or cleaned. But the old buildings remain, even though with a cleaner look. But nothing seems to have been torn down. I saw just one small building with flaking light-colored paint (in Google Earth). And that bulding will probably not be there for very long.

I don’t think that today, in gentrified Butte aux cailles, there would be any little old woman swinging her salad basket on the sidewalk in rue Jean-Marie Jégo.

In 1976, we had to move. We hated to, but we were renting at that time, and the owner had decided to sell the apartment to somebody else without even consulting us. There was nothing we could do to buy the apartment ourselves.

___________________

At l’Ecole Centrale, the students did not seem like anything of the future technocrats they were probably destined to become. They were intelligent, had a good educational standard and the only reason we “native” speakers were wanted was because they are not taught to speak English in French lycées. They could read, they could even write quite well, they understood me without any apparent difficulty, but they didn’t dare open their mouths to speak, probably for fear of making mistakes. I had to let them understand that it was all right, they could make their mistakes, as long as they spoke in sentences. I tried hard not to correct every little mistake they made. The important thing was to make them speak and they must not feel discouraged.

When I completely failed to understand what they were saying because of horrible pronunciation – everybody in the class understood since they were used to this way of speaking – I once asked them if their teachers had never corrected their pronunciation. The answer was a clear No. Their French teachers probably didn’t pronounce much better themselves – or that was at least my conclusion at the time. I have known many good French English teachers since then however . In the case in question it was such a horrible mangling of the word ‘her’ that I had no idea what the student was saying. It sounded more like ‘air’ than anything else. But it has to be added here that things are gradually changing for the better — but too slowly.

It’s a bit scary for a whole country to fail so miserably in the teaching of the most widely spoken language in the world (Well, except maybe for Mandarin, which doesn’t serve a fraction of the usefulness that English does — in fact none at all outside of China, to my knowledge). An awful lot of French people, even educated ones, simply resist learning English properly. It seems to us foreigners as if they just did not want to learn to speak English, but I think it would be more exact to talk about lack of motivation as being at least partially the fault of the teachers.

Since I grew up in Sweden with very modern Swedish language teaching programs and could speak English quite freely after a couple of years in what would be called junior high school in the U.S., the French system seemed perfectly medieval to me. Granted, I probably had such a unique English teacher that she might well have been the best one in the entire country. And I had her for six years in a row. The last couple of years in Gymnasium, I remember lying in bed before going to sleep and thinking in English. Of course I was highly motivated, but it seems to me that so were we all. It’s mainly the teacher who makes for motivating the students, after all. The French won’t admit this. They insist that I must have been especially motivated. Okay, don’t blame your own teachers, don’t blame the educational system. It’s the students’ fault if they are not motivated. Can you really believe such an absurdity?

Our animals in Paris — rue Caillaux

ngg_shortcode_0_placeholder” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

___________________

And this is where Roberto makes his entrée.

Roberto is Paris and Paris is Roberto. The little dark-haired, sometimes mustachioed, Argentinian man invaded our lives completely. He was us and we were him. Whenever I think of our apartments in Paris, it’s with Roberto. Whenever I think of our primitive fermette dans l’Indre, not far from les châteaux de la Loire, it’s with Roberto. When I think of such and such a piece of music, I often think of how Roberto liked it or didn’t like it. His wit, his total absence of any kind of pretentiousness or ambition, his sensitivity, but above all his sense of humor made him unique. He knew about everything without ever having received a university degree of any kind. He started some subject but got bored immediately and dropped out. He had friends who were well-known intellectuals in Buenos Aires but who lived in Paris. One of his friends was the Italian writer Italo Calvino, who lent him his house in northern Italy over a summer vacation, including the chauffeur and the staff of servants.

Roberto tutoyer’ed everybody. I can not ever remember his saying vous to me, even when I barely knew him and, funniest of all, I barely understood his heavily accented French. At first I thought I would never get to understand this funny little Argentinian guy. After some time I didn’t even think of it as a foreign accent. It was Roberto, that’s all. He never learned to say comme in French. It was always como in Spanish.

He was an ardent music lover and a good pianist, and he could usually afford to rent a piano.

One day at the beginning of his many-years stay in Paris, he was at l’Ecole Polytechnique for some reason. Maybe he worked there. I don’t know. He had just met a well-known physicist, Patrick, at “l’X“, which is the common nickname of this highly renowned school. Roberto was walking around leisurely whistling to himself. Since he was always a great talker, he felt like striking up a conversation and he asked Patrick “Aimez-vous la musique?” Patrick thought for a couple of seconds and then said “Je suis plutôt contre.” (If anything, he disapproved of music.) Obviously Patrick was far from being serious, but was just searching for a witty answer to a somewhat simplistic question.

John and I will never forget that hilarious answer, and it keeps coming back in our kidding.

But the outstanding physicist Patrick and Leprince-Ringuet himself, the most notable professor and the director of the physics department at Collège de France, a pioneering particle physicist as well as a notable intellectual (membre de l’Académie française!), were probably about the only people Roberto did not tutoyer. Possibly not Marie-Madeleine either though, who was a wonderful even though religious woman and the personal secretary of Le Prince-Ringuet. Whenever John needed some papers renewed at the Prefecture de Police, Marie-Madeleine went with him and it was Sesame open. She mentioned the name of the most honorable professor and everything was done in a few seconds. Marie-Madeleine was easily the second most prestigious person at the Collège de France. The funniest thing about her, this very religious woman, we discovered once when we were at her very patrician home. She kept her scotch and another bottle or two in a prie-Dieu, as I am told those things are called, where they kneel and say their prayers.

____________________

Roberto had found a job as an assistant in something or other at le Collège de France via a friend of his. As what, I don’t know exactly. Non-physicists as well as physicists in those days worked to verify reactions observed in bubble chambers and maybe Roberto had a job to work with those. Today bubble chambers are gone and immensely more sophisticated and expensive machinery is used to record particle collisions.

Everybody loved Roberto. The physics lab at Collège de France would not have been the same had not Roberto been there to cheer up everybody and everything, whistling a theme from a Brahms symphony or a Beethoven piano concerto and kidding about just anything. I guess you could say that he didn’t take anything seriously. But you can never hold that against him, because he was Roberto.

I remember vividly one time with two common friends of ours, the man a professor of Econometry, Alberto, and his wife our very dear friend Esther, a beautiful Brazilian artist photographer. Roberto wowed about Sao Paolo, the beauty of it, the marvels of this heavenly city. It so happens that Sao Paolo was exactly Esther’s city, where her father still lived, but that’s beside the point. I was a bit curious about his enthusiasm and asked him “Did it never disturb you seeing all the horrible poverty in this city or the surrounding shantytowns, the beggars, the children who barely had any clothes to wear and were constantly asking for a hand-out?” Roberto said “Siv, tu ne comprends pas.” That was Roberto. I should have expected it. Our friend Alberto said: “Non, Roberto, c’est toi qui ne comprends pas. ” Well, I have loved our friend Alberto ever since that day, and John kids me about it. He calls Alberto the second man in my life.

A little corner of our party for Roberto. George-Alberto on the left and Danielle Génat on the right. The cigarette belongs to great friend Jean Huc.

But Roberto had a perfect right to give his opinion of course. Roberto was … Yes, I must now say, my eyes tearing up some, that he died very suddenly of a heart attack about two years ago. No pain, says Marta, his lady friend for many years, whom we also loved, a wonderful woman. He just keeled over at the breakfast table.

He will never be dead to me and it’s difficult to remember to use the past tense. So Roberto was passion, he was an intellectual and a great music lover of course, but he was a lover of life above all. He did what he pleased, as long as he didn’t hurt anyone. He would be totally incapable of hurting anyone. He would never ever have put me down for my very leftist political views. In fact, he was totally indifferent to politics, since he most likely thought it was all a sham.

He respected me for who I was and there was mutual love and respect – love meaning so much more than sexual love. It’s sad how often people confuse love and sex, since very often they don’t even overlap.

He moved back to Buenos Aires in the early eighties, and we of course had a party for him and all our common friends. Our living room was crowded. Esther was also there of course. She too had, before marrying Alberto, an assistant job at le Collège de France.

But he came back. He came to Paris once with a woman friend whom we got to know very well, and like a lot. He has also been to see us here in Genas, our suburb of Lyon, three times, once with his wonderful and lasting partner, Marta. And we went to see them in Buenos Aires, or BAires, as Roberto always wrote. That was in 1990, an unforgettable trip. But that is another story.

Continued: Chapter 24 (Part 1) – Arne and Drottningholm Theater