Chapter 10 – Stockholm theater

I have already mentioned a few of the high points of theater from my youth, first of all seeing Poul Reumert and Bodil Ipsen in ‘Tartuffe’ at Det Kongelige in Copenhagen when I was just 15, but also ‘Antigone’ on the small stage (Intiman) at Malmö Stadsteater, Strindberg’s ‘A Dream Play’ on the main stage, a superb production by the legendary Olof Molander, guest from Dramaten, the outstanding interpreter of Strindberg plays, and with Inga Tidblad as Indra’s daughter. There was ‘Peer Gynt’ by Henrik Ibsen, quite a few years later, when I was already at the university, directed by Ingmar Bergman with Max von Sydow and Naima Wifstrand in the lead roles. I would add to this, however, that I wish Ingmar Bergman had been less ambitious and had not opted for producing the almost uncut play, which lasted five hours. I do admit though that it was five hours of intense theater.

But I am going to take a step ahead into the years after my high-school graduation (studentexamen) and after my first stay in France. There has been so much beautiful theater in my life that, if I were just a little more knowledgeable about Swedish theater, the actors, the directors and the plays, I could have written a book about just that topic. I saw many wonderful performances at the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm, among them ‘The Three Sisters’ by Chekhov in 1959 with Bibi Andersson and Anders Ek; Hjalmar Bergman’s ‘His Lordship’s Last Will’ (Hans nåds testamente) with Olof Sandborg, one of the most outstanding Swedish actors of his generation, as His Lordship, baron Roger Bernhusen de Sars, and Elsa Carlsson, annther one of this theater’s leading actors, as the widow of he Dean.

Nybroviken, seen from the Royal Dramatic Theater — lots of sightseeing boats leave from here on their various tours around “the Venice of the North”.

t saw ‘His Lordship’s Last Will’ in 1961. The novel by the same title was published in 1910, and Bergman subsequently dramatized it himself. A Swedish movie was made in 1919 with the inimitable actor Victor Sjöström — famous for my generation as the old professor in Ingmar Bergman’s wonderful movie, “Wild Starwberries.”

Hjalmar Bergman died in 1931 in Berlin, less than 50 years old, a total wreck, an alcoholic and a cocaïne addict.

Hjalmar Bergman is one of my absolute favorite Swedish writers, simply outshining all other writers of his time, except I suppose, Strindberg, but oh so different. Hjalmar Bergman is essentially a novelist, but one with his own magic imprint. When his novels were dramatized, it was to my knowledge done by himself. He had a great sense of humor, something Strindberg was, it seems to me, sadly lacking.

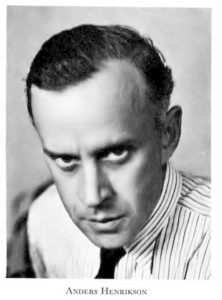

I saw Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’ in 1962 on the small stage of Dramaten, directed by Per-Axel Branner, a superb performance with Olof Widgren and Gunn Wållgren. Equally on the small stage there was ‘The Miser’ (‘Den girige’,’ L’Avare)’ by Molière in 1961, with my much beloved actor, Anders Henrikson, as Harpagon. The director, Stig Torsslow, I knew well from Malmö Stadsteater where he was the administrative director and an excellent stage director from 1947 to 1950. He had now moved to Dramaten and he was one of the two outstanding experts on O’Neill. He did a wonderful mise-en-scène of this play. I have also seen l’Avare at La Comédie-Française in Paris (1962, mise-en-scène by Jacques Mauclair), a very gripping performance, but definitely staged more as a tragedy than as a comedy.

________________________

Among the most remarkable,or even historic, performances that I saw, at the Royal Dramatic Theater (usually called Dramaten) and that I remember the most vividly, was Henrik Ibsen’s “The Wild Duck” (Norwegian and Swedish – “Vildanden“) and maybe above all Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey into Night”, which had its world premiere at the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm in 1956. This is definitely theater history. I get back to “The Journey” further down.

I saw “The Wild Duck” twice, once with my friend Britt (who, always generous, invited me I believe) in 1955 on a visit to Stockholm, with Eva Dahlbeck and Ulf Palme (not to be confused with Olof Palme, the Swedish Prime Minister who was assassinated in 1986), directed by the most remarkable stage director Alf Sjöberg, who has gone down to Swedish theater history as a monumental director.

The main theme of “The Wild Duck” concerns Hedvig (played by Margit Carlqvist) and her being the real daughter of the rich wholesale dealer Werle, not of her legal father, the photographer Hjalmar Ekdal. It’s the enormous tragedy of Ekdal and of Hedvig when it finally becomes clear to him that his adored Hedvig is not really his daughter and he denies her his love. Hedvig has inherited an eye disease from her real father, the rich man Greger Werle who is nearly blind. It’s a story of a family living on a lie (en livslögn). Hervig doesn’t understand why her father shies away from her, and she ends up jilling herself.

The same theme, curiously or not, comes back in several Scandinavian literary works, above all in Strindberg’s play “The Father“. There is Hjalmar Bergman’s novel “Markurells of Wadköping“, dramatized by Bergman himself and translated into English, that deals with the same lugubrious theme in a masterful way, even though very differently. The farcical but also sad innkeeper, Markurell, ends up accepting the truth, thus avoiding a looming tragedy. Hjalmar Bergman never forgets the touch of humor in his vast number of novels, a mixture of humor and tragedy. I saw rhis play, a wonderful performance in Malmö in 1945, and even though I was just 12 years old, I still remember Anders de Wahl as Marjurell aqd Stina Ståple som frun Markurell. The play was directed by Sandro Malmquist, at the time the director of Malmö Stadsteater.

However, the character that fascinated me the most in ‘The Wild Duck’ was Doctor Relling played by Anders Henrikson, the inimitable great actor of those days. I will never forget his stand, his voice, his look in a side story to this lugubrious play. This elderly doctor is trying to save a young man, Molvik, from a lifelong depression and feeling of worthlessness, by trying to convince him that he is a demon. On the stage that was divided into two parts, we see Relling and Molvik in a room on the left, Relling repeating to his protégé “Molvik är demonisk”. It takes a superb actor like Anders Henrikson to give this simple line its full weight, but Henrikson does it with a dramatic bravura that is impossible to forget. I can recall it at any time and it always gives me goose bumps to ‘hear’ his way of delivering this line that’s stored in my mind. His wonderful voice and the eerie stress he put on the lengthened second syllable of ‘demooonisk’ made that line rivet itself into my memory.

Quite a few years later the play was put back on the stage and Arne and Mother invited me and my husband, Roland, to see it. The cast was the same, except for the daughter who was now played by Christina Lundquist, also excellent. I can never forget how Roland got so moved and upset by the tragic story that he actually completely lost his temper. He said to me (we were not sitting next to Arne and Mother, fortunately) that it was unforgivable to write and stage plays with such ghastly themes.

_________________________

“Long Day’s Journey into Night” by Eugene O’Neill is probably one of the most superb theater performances I have ever seen. That was in 1956 and it was directed by Bengt Ekerot. As I remember I saw it with Arne. Lars Hanson played James Tyrone and Inga Tidblad his drug-addicted and mentally disturbed wife. O’Neill’s plays have a long and famous history in Sweden, and for his last plays this very special reputation was due to Karl Ragnar Gierow, director of the Royal Dramatic Theater 1951-1963, and a member of the Swedish Academy.

In fact, it was not clear at one time that the last few plays even existed, since O’Neill himself had firmly told the press that there were no plays left behind, contrary to existing rumors. Of course they were found, but in the unwieldy version Gierow received them after O’Neill’s death in 1953.

It was the second UN secretary general, the Swede Dag Hammarskjöld, who acted as a go-between for Gierow and O’Neill’s widow, Carlotta Monterey O’Neill. It was not, as it has been claimed by some sources, against O’Neill’s own wishes, that Gierow adapted his latest plays for the stage. Among other things, they had to be very much shortened to become finished theater plays. O’Neill had the highest regard for the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm since they had a long history of masterful first performances of his numerous former plays. O’Neill clearly stated to his wife, Carlotta, a few days before he died, that he wanted The Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm to have the world premiere for ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’

“July 22 — On this day in 1941, on his twelfth wedding anniversary, Eugene O’Neill presented the just-finished manuscript of Long Day’s Journey Into Night to his wife, Carlotta. Accompanying the manuscript was O’Neill’s letter of dedication: ‘Dearest, I give you the original script of this play of old sorrow, written in tears and blood. A sadly inappropriate gift, it would seem, for a day celebrating happiness. But you will understand. I mean it as a tribute to your love and tenderness which gave me the faith in love that enabled me to face my dead at last and write this play — write it with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones. These twelve years, Beloved One, have been a Journey into Light — into love….”‘

This letter of dedication to Carlotta is included in the program from 1956 by Karl-Ragnar Gierow, along with his essay about the O’Neill family, which is the background for “The Journey”.

Karl Ragnar Gierow took it upon himself to deal with the enormous task of transforming this extremely long and autobiographical work, that O’Neill himself had clearly given up on, into a play of a more reasonable length that would be possible to perform. Gierow and Carlotta O’Neill had a lively correspondence and met several times to discuss the completion of O’Neill’s latest plays. “Karl Ragnar Gierow flew to New York several times, and the two developed a mutual admiration and friendship.” [1. Brenda Murphy: O’Neill: ‘Long Day’s Journey Into Night’. Brenda Murphy, a Northern Ireland playwright, seems to be the only anglophone source for any mention of Karl Ragnar Gierow’s tremendous accomplishment in the adaptation of this unwieldy tragedy of 8 hours into a heartrending 4-hour play. In fact, on further search I find an article in the New York Times from February 19, 1956 which credits Karl Ragnar Gierow with being the producer of the play, but without any details about the enormous task Gierow had taken upon himself of rendering this masterpiece playable, which he had managed so very successfully.]

ngg_shortcode_0_placeholder

To make “Long Day’s Journey into Night” possible to perform, Gierow, with Carlotta’s full agreement, had to reduce the length of the play drastically. He finally managed to cut down the 8-hour play to four hours. “Long Day’s Journey into Night” was, as someone has said, “unashamedly autobiographical”. O’Neill had earlier let it be known that it could not be performed until 25 years after his death since it was so very close to reality. However, a few days before his death he changed his previous stipulation and expressed his desire that “Long Day’s Journey” be performed at the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm.

This change of heart is taken almost word for word in translation from Karl Ragnar Gierow’s fascinating essay about the play and about the O’Neill family in the program of ‘Lång dags färd mot natt’, which premiered in February 1956. There is also a complete list of the nineteen former O’Neill plays that had been performed at Dramaten.

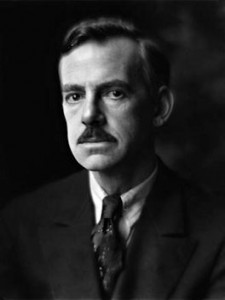

Lars Hanson, the actor who played lead roles in several O’Neill plays at Dramaten. (Photo Dramaten program)

“Long Day’s Journey”, translated by Sven Barthel, opened at the Royal Dramatic Theater in February 1956, in Karl Ragnar Gierow’s abridged version and under the direction of the very young Bengt Ekerot.

The play “A Moon for the Misbegotten” is to some extent a sequel to “Long Day’s Journey into Night”. It was clearly easier for O’Neill to get the sequel finished, probably because it was far less autobiographical..”The Moon” had its premiere in the United States in 1947, but it was not a success. It took a couple of decades for the American public to realize that it is one of O’Neill’s best plays. He began writing both plays in 1941, but he only completed “A Moon for the Misbegotten”, whereas “Long Day’s Journey” was never finished by him.

The tremendously important role of Karl Ragnar Gierow in the final and playable version of “Long Day’s Journey” sadly seems to have been forgotten by later producers of this play.

Later on, Gierow did the same kind of arrangement, with Carlotta’s blessing, of O’Neill’s very last play, “Build More Stately Mansions” another enormous undertaking. I saw that play at the Broadhurst Theatre on Broadway early in 1968. (Its American premiere was in April 1967 at the Ahmanson Theater in Los Angeles) with Ingrid Bergman as the lead character and in the direction of José Quintero.[1. “More Stately Mansions” by Eugene O’Neill; Starring Ingrid Bergman, Arthur Hill and Colleen Dewhurst; Directed by Quintero. “Build More Stately Mansions” (“Bygg allt högre boningar”) had its world premiere at Dramaten in November 1962, finished and abridged by Karl Ragnar Gierow. (Inga Tidblad, Gunnel Broström Jarl Kulle); direction by Stig Torsslow)]

From The Spectator: “EUGENE O’NEILL was appreciated in Sweden when neglected almost everywhere else — something he never forgot. On his death, in 1953, he willed his three unpublished plays, “Long Day’s Journey into Night”, “A Touch of the Poet”, and “Hughie”, to the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, where they had their first performances between 1956 and 1958. A fourth, unfinished work was discovered in 1956. This was “Build More Stately Mansions”, which had its world premiere, also at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, last Friday (November 1962).”

It was of course interesting to see Ingrid Bergman on the stage, with her phenomenal stage presence — and a slight Swedish accent — but actually the play did not impress me. Even without O’Neill’s direct permission, his widow, Carlotta, authorized Karl Ragnar Gierow to turn this unfinished work into an acting version and it had its world premiere at Dramaten in 1962.

When, later on, I told Arne that I didn’t particularly like the performance on Broadway, he said that it wasn’t a very good play to begin with. He may or may not have a point there, but it is a fact that I was not very impressed. It had nothing of the riveting force of the performance I had seen of “Long Day’s Journey into Night” at the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm in 1956.

Panama-born American director José Quintero was the one who revived interest in Eugene O’Neill, starting in 1956 after a decade of near oblivion. He got Carlotta’s permission to stage “The Iceman Comethh” at the fledgling theater Circle in the Square in Greenwich Village.

Quote from ‘Lifelong Love Affair With O’Neill Works’ (LATimes)

“Quintero’s production of “The Iceman Cometh” was a now-legendary smash, almost single-handedly restoring O’Neill’s flagging reputation in the United States, adding momentum to the burgeoning off-Broadway movement, making a star of a young actor named Jason Robards Jr. and setting the stage for the director’s lifelong love affair with the works of the playwright.”

_____________________

The performance I saw in 1956 of ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’ was, I believe, the most mesmerizing performance I have ever witnessed. The actors were Inga Tidblad, Lars Hanson, Ulf Palme, Jarl Kulle and Catrin Westerlund. I knew Inga Tidblad from guest performances at MalmöStadsteater, and, as always, she was magnificent. In fact, everybody knew Inga Tidblad.

Lars Hanson was one of the most outstanding Swedish actors of all times. He had spent periods in the USA. and also in Germany performing in movies, and he had also done guest performances in Oslo, Copenhagen and Helsinki. During the period 1925 – 1928 he had lead roles in six Hollywood movies against Greta Garbo and Lillian Gish. He returned to the stage however, and received the Eugene O’Neill Acting Award in 1956 — with Inga Tidblad — the year he played James Tyrone in “Long Day’s Journey”. When he died in 1965 during the years I was living in the United States, the New York Times had an obituary about him. I was impressed.

Arne used to say that Lars Hanson was the most superb actor ever but that he couldn’t understand a word of what he was saying. Well, Arne was prone to dramatic exaggeration, and I can’t remember that Lars Hanson’s diction bothered me. Be that as it may, it was an extremely moving performance, reflecting the personal pessimism that pervades most of O’Neill’s plays. O’Neill was during his whole life subject to depression and emotional instability.

Inga Tidblad and Lars Hanson are at the very top of the Pantheon of Swedish theater from the mid-20th century. Ulf Palme and Jarl Kulle, the two sons in O’Neill’s play, are both well known to fans of Ingmar Bergman movies.

Olof Molander – I mentioned him as the superb guest director of Strindberg’s ‘A Dream Play’ at Malmö Stadsteater in 1947 – and the equally outstanding Alf Sjöberg, who was the director of “The Wild Duck” at Dramaten were two of the main pillars of Swedish theater, from the generation before Ingmar Bergman became an icon to cinema lovers the world over.

Both Sjöberg and Molander also directed a vast number of movies. The one I remember the best is Strindberg’s “Mademoiselle Julie” (Fröken Julie) by Alf Sjöberg, by far my favorite play by Strindberg. I saw it in Luxeuil with my great friend Gaëtane, dubbed into French of course, the way all foreign movies were in those days. That was in 1952 and the movie was made in 1951. How amazing that the little town of Luxeuil-les-Bains had found the way to a very recent Swedish movie, and an excellent one at that. Since I knew the play I don’t think the dubbing bothered me much. The movie had actually won le Grand Prix du Festival de Cannes in 1951, which I didn’t know at the time.

I loved the movie and it was really so funny seeing this masterpiece by Strindberg in a little French town with a French friend. It was a bit like tuning in a Swedish radio station on our radio at midnight on New Year’s Eve in 1952 and listening to the great actor Anders de Wahl read with a thundering voice (a recording actually at that time, and de Wlah died a few years later) Nyårsklockan – Ring, klocka, ring… And after de Wahl‘s reading of this poem by Alfred Tennyson [1. Ring Out, Wild Bells / Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky, / The flying cloud, the frosty light; / The year is dying in the night; / Ring out, wild bells, and let him die./ Ring out the old, ring in the new, / Ring, happy bells, across the snow: / The year is going, let him go; / Ring out the false, ring in the true. / Ring out the grief that saps the mind ], you hear the church bells of innumerable Swedish churches from all over the country. I was not extraordinarily sentimental about my homeland even at the time, but it was a strange and also fun experience getting a whiff of Sweden on this special night far away from home.

Continued: Chapter 11 — Marriage and teaching