Chapter 28 (Part 2) — Thirteen years in Paris; Theater and Music

During those thirteen years in Paris we of course went to see many operas, concerts and theater productions.

One of the performances that stand out the clearest in my memory is Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” and the extraordinary voice of Galina Vishnevskaya, a very Russian soprano. The music is based on poems by Wifred Owen. Britten is said to have been entranced by the voice of Galina Vishnevskaya. Who would not be? But he was clearly first entranced by Wilfred Owen’s war poems. Wilfred Owen, the war poet who died in the cruel first world war just a few days before the armistice was signed. Has there ever been a war that was not cruel? Of course not. But in this particular war half of a generation of English, French and German young men gave their lives — for what? For the pride and greed and lust for power of rulers of nations and the “glory” of the “fatherland”.

This reminds me also of a stark autobiographical novel by Vera Brittain: “Testament of Youth“, which makes you feel so much the cruel meaninglessness of war.

The performance at the Salle Pleyel in January 1979 was profoundly moving. The horrors of war come through starkly in Vishnevskaya’s incredibly dramatic voice. Her husband, Mstislav Rostropovich, the masterful cellist whom we had heard previously somewhere, was now the conductor. It was altogether a fascinating and incredibly gripping performance. And it was also live history.

I have somehow mislaid my program for this wonderful concert, and the two things I am sure of is the names of those two stars performing together, the way they often did on international tours.

The premiere of the “War Requiem” was in 1962 at the Coventry Cathedral, Coventry, West Midlands. It is a choral work with three soloists, whom Britten selected with a sure mind. It was supposed to be Galina Vishnevskaya, soprano, Peter Pears, tenor and Dietrich Fischer Dieskau, baritone. Well, it was supposed to have been, but Vishnevskaya was not there. At the concert we attended at la Salle Pleyel, the tenor and the baritone were sung by other men, and I don’t remember who they were. But the concert was heartbreaking and unforgettable.

Vishnevskaya had been prevented by the Soviet authorities from going to Coventry for the world premiere of “War Requiem” in May 1962. However she took up the role that Britten had created for her at the Royal Albert Hall the following January. She also sang the part in the first recording ever made of the “War Requiem” that same year, with the trio Britten had in mind from the beginning.

Britten’s music is based on nine of Wilfred Owen’s anti-war poems. The most striking words that are remembered by many of his readers are certainly how proud Abram slew his first-born son Isaac, in spite of the angel having told him to sacrifice a ram instead of his son.

The angel says to Abraham:

“Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so,

but slew his son, –

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”[7. The War Poetry of Wilfred Owen:

“When lo! an angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him. Behold,

A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns;

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so,

but slew his son, –

And half the seed of Europe, one by one”]

“Benjamin Britten wrote the soprano role in his War Requiem (completed 1962) specially for Vishnevskaya, though the USSR prevented her from traveling to Coventry Cathedral for the premiere performance. The USSR eventually allowed her to leave the country in order to make the first recording of the Requiem.” (Wikipedia)

From 1973 to 1986, I taught advanced English literature and civilization classes at l’Ecole Centrale de Paris, and, since I was myself deeply moved by Owen’s war poems, I had my class read some of them. I still remember the lines

“Move him into the sun –

Gently its touch awoke him once,”

I loved Britten’s music and after having a class of mine read Wilfred Owen’s poems I decided I wanted to let my students listen to the music too. I brought in the LP — at some time around 1980. After a brief introduction of Britten, I warned them that Vishnevskaya had a very special Russian soprano voice, superbly dramatic, and that they should not compare her to a western soprano.

I sensed how immersed they were in the music. Some of them put their heads down on their desks and you could have heard a pin fall in this complete silence from my students. It was like a sudden transformation of my classroom into a cathedral.

________________

In 1975 we saw, once again, the absolutely spellbinding ballet, Petrushka, by Igor Stravinsky. It was of course at the Opéra de Paris and we invited our niece Kajsa to come with us to this extraordinary performance. She was in Paris doing her first year of French studies at the Sorbonne.

Adding greatly to the enormous success of the performance was the décor by the Russian artist, Alexandre Benois. He died in 1960, but his sets and costumes for several ballets have gone down to history. His artistic work was one of the essential factors that accounted for the enormous success of the first performance in 1911.

The music of Petrushka may just be my favorite of all the wonderful music I love — and that is saying a lot.

The choreography was, as it had been in New York City in 1972, still said to be by Michel (Michail) Fokine, the version he did for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1911 in Paris at the Théâtre du Châtelet. The scene is set in 1830 at the Shrovetide Fair (carnival, analogous to the carnival of Mardi Gras in New Orleans) celebrations taking place in Saint Petersburg. The opening scene shows crowds of people at the fair in Russian period costumes, milling around and playing out various funny little scenes in the crowd.

Scene from the 1975 performance of Petrushka at the Paris Opera — Nureyev and Pontois in the foreground

On a given signal the crowd moves off the center stage. The magician looks out through the curtains of his puppet theater, he steps out, the curtains move aside, and with his wand he makes the puppets (pantins, since this ballet was first performed in France) come alive and start dancing, all the time acting like the puppets they are supposed to be. In the following scenes, no more puppets now, we find that Petrushka is madly in love with the ballerina, who rejects him. She prefers the supposedly dumb Moor.

The one important difference from the ballet we saw in 1972 by the Joffrey Ballet at the City Center was Rudolf Nureyev performing as Petrushka, dancing and acting. The way he and also the other two major characters, Noella Pontois and Charles Jude, act out a mime show while performing magnificent ballet is amazing. Petrushka is miming his love for the ballerina in almost heartrending gestures. After the ballerina appears in his room and soon disappears again, his grief is almost palpable. Nureyev’s mime performance is definitely in the class of Marcel Marceau and here the same trick is used as by Marcel Marceau,[8. Chapter 18 (Part 1) – Mamaroneck High School and friends] feeling around the walls which are not there, in a way that makes the audience feel that there are indeed walls around the room.

The mise en scène of the tableaux of festive people at the carnival, which we get back to after the scenes in the rooms of Petrushka (Tableau 2) and the Moor (Tableau 3), at the carnival is equally superb, complete with bear and all.

Yves-André Hubert filmed them for Antenne 2 TV channel, which broadcast the ballet on December 27th 1976.” (Nureyev dancing in Petrushka) [9. Nureyev & Pontois in Petrouchka 1976, the entire ballet;te]

________________

Another fascinating show during our years in Paris was George Gerswin’s “Porgy and Bess”, with libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It is one of my favorite operas ever, which is in fact a meaningless statement since it can not ever be compared to Mozart, Verdi, Puccini or Richard Strauss. (John says I forgot to mention Wagner, whose operas I do not like, even though we went with Arne to see Tannhäuser in Stockholm — in Swedish, no less.) It is an entirely different kind of production and there are even spoken parts in the libretto.

“Porgy and Bess” was created in 1935 and it was first performed in Boston on September 30, 1935, before it moved to Broadway in New York City.

“It featured a cast of classically trained African-American singers — a daring artistic choice at the time. After suffering from an initially unpopular public reception due in part to its racially charged theme, a 1976 Houston Grand Opera production gained it new popularity, and it is now one of the best-known and most frequently performed operas.”(Wikipedia)

Porgy And Bess (Original soundtrack) Jacket of DVD for production premiered in 1976 Houston Opera

The Houston Grand Opera toured Europe with its spectacular production of “Porgy” in the late 70s. It began with a six‐week engagement at the Palais des Congrès in Paris, sponsored by the Paris Opera. Metteur en scène was Jack O’Brien.

We saw this stunning production in early 1978. Actually, we saw it twice, the first time with John’s parents and with his aunt and uncle, Ann and Larry, classic opera lovers. Later on, my sister Gun visited us and it seemed like a must to go back and see it once again with Gun. I could not see it too many times anyway. It was with a different pair of lead singers the second time. The quality of the show was of course the same. Superb [10. “The role of Porgy in the Gershwin opera will be taken alternately by Donnie Ray Albert and Robert Mosley, that of Bess by Wilhelmenia Fernandez and Naomi Moody.”(Houston Opera’s ‘Porgy’ To Tour Europe)]

The production was magnificent. You felt as if you were in the U.S. South, Alabama, Georgia, or some such genuinely southern state. In fact, the opera takes place on Catfish Row in Charleston, South Caroline. The singing and acting were the very best. In an opera like this one, the acting is more important than in any 19th century opera I can think of.

The short but rousing overture set the mood right away, then calmed and led into the very first song, Clara singing a lullaby, “Summertime” to her baby whom she is holding in her arms.

Summertime / And the livin’ is easy / Fish are jumpin’ / And the cotton is high / Your pa is rich / And your ma is good-lookin’ / So hush little baby / Do-on’t you cry-y . (George and Ira Gerswin — Summertime — Harolyn Blackwell) — Wonderful. Clara’s husband, Jake, sings his child a lullaby of his own — “A woman is a sometime thing”.

The story is a combination of a love story and a stark drug drama. Sportin’ Life is a drug dealer and he is trying hard to get Bess away from Crown, her “man”. Porgy is a crippled man and at the beginning he sings about himself as being doomed to a lonely life. But he senses that Bess has feelings for him and the story evolves. You were almost moved to tears when Porgy and Bess were singing Bess you is my woman now. Bess is responding very warmly. She never had any love for either Crown who abused her or for Sportin’ Life.The final scene is unclear, as it should be, but it leaves you with hope for a good ending.

Bess does not want to have anything to do with Sportin’ Life and his drugs any more. However, Sportin’Life is a clever drug dealer and he knows how to win over unwilling persons. He sneaks up to Bess’s door and puts a little package of dope in front of the door.

The next thing you know is Bess leaving with Sportin’ Life for New York City. But Porgy is not going to put up with being the loser. He gets in his goat-cart and prepares to follow Bess as the curtain falls. The final note is one of hope for Porgy and hope for Bess who loves him.

I don’t know who played Sportin’ Life, but his singing and acting of “It ain’t necessarily so” was perfect. “Oh Jonah he lived in a whale / Oh Jonah he lived in a whale / He made his home in / That fish’s abdomen / Oh Jonah he lived in a whale” — What a wonderful Ira Gershwin rhyming!

_______________

We saw the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater with the striking dancer and actress, Judith Jameson. This time we were with John’s sister Marjie, and it was in June 1975 at the enormous hall, le Palais des Sports, also called le Dôme de Paris, close to la Porte de Versailles. The dancers also did a ballet to the music of Carmina burana, Carl Orff’s rousing musical composition based on sundry texts in low German and Vulgar Latin from the centuries before what we call the MIddle Ages.

We had seen Alvin Ailey in New York City with our niece Kajsa in the early summer of 1973, but it was wonderful to see these magnificent dancers perform this monumental piece of music. [10. I talk about the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater at some length in Chapter 22 – An active year with John in New Rochelle.]

_______________

Now over to some of the great number of more classic operas we saw in Paris. Apart from all the Mozart, Verdi, Puccini and Strauss, one that I remember well is “Tales of Hoffman” (Les Comptes d’Hoffman) by Jacques Offenbach, in 1974. Arne was with us that time and it might well have been the time he had traveled to Paris with one old shoe and one new one. We dressed up to go to the opera in those days; for me usually a long skirt and a nice blouse.

I remember Hoffman, sung by Nicolai Gedda, the Swedish tenor, standing on a table in the first act singing “Kleinzach”. Fires were burning on the front edge of the table and I was just hoping Hoffman’s long black robe would not catch fire. But of course, as John said they were of course not real fires. Hmm. I have always liked The “Tales of Hoffman”, ever since my youth, and I think there was even a movie made of this opera many decades ago.

We did in fact also see “Tales of Hoffman” in New York City at the New York City Opera with wonderful Beverly Sills singing all three female roles, the way I think it should be done, since they are all three figments of Hoffman’s dreams.

We also saw a Richard Strauss opera “Salomé” and, even tough I find his operas a bit difficult to take (unless it is “Der Rosenkavalier”), I liked “Salomé”, a very dramatic and gripping story and opera, even though pretty horrible, as is the case in lots of classic operas. Anja Silja, the great German soprano, was a wonderful Salomé.

We also saw, by Richard Strauss “Die Frau ohne Schatten“, which was the loudest opera we have ever seen. John comments that he is sure that at one point the chandeliers were shaking. We don’t remember any other details from this performance, and I clearly don’t have a program.

We heard Placido Domingo, who is usually considered to be one of the foremost tenors of our time. We like him possibly even better than Luciano Pavarotti. We also heard Placido Domingo in Puccini’s “Tosca” singing Mario Cavaradorossi in this murderous tragedy and in Verdi’s “Il Trovatore” singing Manrico, a most confusing and frightful story about revenge and death.

I have already in Chapter 24 talked about the production of “Le Nozze di Figaro” at l’Opéra de Paris in 1974, and I will just add a few things here. Teresa Berganza, the Spanish mezzo-soprano, for me, is magic. I am so much in love with her voice that I just soar when I hear her sing a special aria from Rossini’s “La Cenerentola”, “Una volta c’era un re”. (Cinderella — Once there was a king) The rest of that opera is not one of my favorites. Here she is as Cherubino singing one of the most famous arias from “Figaro”. Cherubino is in love with the countess, but he has to go away to the army and, sadly, he sings “Voi che sapete que cosa é l’amor“. It was an absolute dream hearing her and I went wild with ecstasy, as I believe did half of the audience. I was standing up applauding until the palms of my hands were actually getting sore. The entire audience was standing up, and the applause seemed to never want to stop. It is not for nothing called “a standing ovation”

In June 1981 we saw “Turandot” by Giacomo Puccini with Montserrat Caballé at the Paris Opera. First I want to tell you about a little episode concerning Montserrat Caballé. My sister Gun was on a transatlantic flight sitting next to a couple who were clearly opera lovers. They brought up the subject of Montserrat Caballé, who was a favorite soprano of theirs, saying that she weighed 200 pounds, but it was every pound in pure gold.

So here I got my chance to hear Montserrat Caballé. She pretty much held up to my expectations. It is just that I am not really a high soprano lover and sometimes she got to be a bit too much for me. I love Puccini, but I found this opera a bit too grandiose, too Wagnerian almost. Puccini’s soprano arias often get to be very demanding, and — Was I wrong? or did Caballé sometimes not quite come up to par? This is, we must know, one of Birgit Nilsson’s most famous roles 13 So no wonder if I sensed Caballé being slightly insecure on her first appearance. She soon found her footing though and I thought she got through the opera with bravura. John and I do agree, however, that Birgit Nilsson or Joan Sutherland in our own recordings beat Caballé on the high notes. As for Birgit Nilsson, my fellow country woman, I am just not really into the kind of grandiose Wagnerian arias she excels in.

However, I do want to mention my one favorite soprano, Renata Tebaldi (‘la Tebaldi”), whom we have never heard live. But I have heard her in several recordings and, with the perfect sound rendition we get today, that is really hearing her. She is always soft even in her high notes, and it is a dream to listen to her. She actually performed at the Met in the 70s when theoretically John and I could have heard her, but getting tickets to her performances was another matter. She was nicknamed Mrs Soldout.

I am reminded of a comment by Arne when I say “grandiose”. I said once to Arne, who, like John, is a Wagner lover, “Don’t you think Wagner is sometimes a bit pompous? ” Arne thought it over and came back with “No, I would rather say that perhaps he is not pompous enough.” Typical Arne come-back.

However that may be, the cruel Chinese princess Turandot finally gets her prince Calaf, sung by Giuseppe Giacomini. This tenor was also a first for me. He was very good, even though I sometimes felt that there was too much vibrato in his voice.

I do want to add that the second soprano, Leona Mitchell, as Liù was wonderful. Liù is a young servant woman who is madly in love with prince Calaf, and who kills herself towards the end of the opera.

In 1974 we saw Puccini’s “La Bohème” my favorite opera ever, if it is possible to claim such a thing. “La Bohème” is in fact the only opera I like to listen to at home, in its entirety. Other operas I prefer to listen to in opera houses. In this production Mimi was sung by Jeannette Pilou and Rodolfo by Carlo Cossutta. I knew neither of those singers before, but they came out with flying colors. We saw it again in Lyon, many years later, and I always love it so much I almost get tears in my eyes at the end. In fact, I adore this opera. We saw it at the Auditorium in Lyon when the opera house was being rebuilt. I remember quite well the scene at the Porte d’Enfer in Act 3. In fact, I remember several scenes from that performance. — or at least I believe that is the one — the final scene when Mimi is dying, but still goes on singing, the same as in Verdi’s two best-known operas, “La Traviata” and “Rigoletto”, which I have seen elsewhere, not with John. I also vividly remember, from the Lyon performance, the scene on Christmas Eve at the plaza, a wonderfully lively scene with people milling around, and where Mimi’s friend, Musetta, gives out a musical scream when she realizes she has lost the heel of her shoe. I can still hear Musetta’s musical scream.

Back to l’Opéra de Paris and “Madame Butterfly,” another wonderful opera by Puccini that we saw during those years. It has been said to have the most beautiful arias (and a duet) in Puccini’s entire work. We are almost sure it was Mirella Freni who sang Madama Butterfly and Christa Ludwig sang Susuki her servant and friend. Here is Mirella Freni. “Un bel di vedremo” (We shall see a beautiful day), Madama Butterfly from Act 2 of the opera. Freni is one of our favorite sopranos and we have seen her in quite a few productions. I remember some scenes vividly from this performance, but I don’t have the program and the cast can not be found on the Internet.

We also saw Mirella Freni in Verdi’s “Simon Boccanegra”, in 1978. one of Verdi’s finest operas. She sang the role of Amélia Grimaldi in this extremely complex opera set in the 14th century when Genoa and Venice were republics governed by a doge.

I have lost the program for this opera as well, but amazingly I find it online and John also remembers most of the important singers and the conductor, Claudio Abbado. On the site it says that Mirella Freni was magic. She was indeed extraordinary. We have always loved her. Piero Cappuccilli was Simon Boccanegra, baritone.The tenor was José Carreras and the great Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass, sang Jacopo Fiesco. This opera was a co-production with l’Opéra de Paris and la Scala di Milano. I just now found that Nicolai Ghiaurov was married to Mirella Freni in a second marriage. Remarkable singers, both — “la magie de la représentation autour d’une Mirella Freni magique.”

We saw one opera at the Lyon Opera before its restoration — an excellent performance of Verdi’s Falstaff. They had the Thames on stage and when the women dumped Falstaff in, he came out all wet. John Elliot Gardiner conducted.

However, we are clearly very strange people. We love opera, but we can not stand the renovated Opéra National de Lyon. To me it looks like a crossing between a bordello and a battleship with its black floor, even see-through, and red color wherever it is not black. We made a one-time visit to the “new” opera, after the renovation. It was a pretty boring production of “The Marriage of Figaro”. But all the time we just felt uncomfortable because of the décor around us. So, apart from quite a few operas that we saw at the Auditorium during the reconstruction, we don’t go to see operas any more. We have also become homebodies with age.

_______________

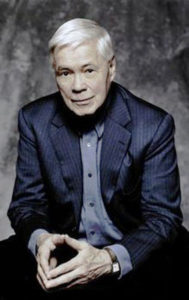

There were also our absolute favorite musical soloists who performed quite often in Paris. There was Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the extraordinarily wonderful baritone whom I associate mostly with Schubert Lieder, but we also heard him sing Lieder by Schuman and also, once, Lieder by Richard Strauss. It was just a dream hearing Fischer-Dieskau sing. He would put his hand on the grand piano and it was the beginning of the dream. Just straight forward and simple, no manières, no show-off, but his singing was out of this world. He sings, no, sang (alas, he died in 2012), opera too, and very much so, but it is always as a singer of Lieder with his right hand on the grand piano that I will remember this wonderful man.

Dietrich Fischer-Diskau Wikipedia

In this picture he looks younger than I remember him, but I never remember him as looking old.[16. Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau, who died May 18, was a unique performer. In a very long career he managed to sing and record almost anything that a classically trained baritone could possibly sing. While best known as the foremost interpreter of German art songs he appeared almost as often in the opera house as in the concert hall. The facts of his life and career are well known and can be reviewed here. He was likely the most prolific recording artist in the history of the medium – not even Placido Domingo comes close. Somehow, he never appeared at the Metropolitan Opera. Their loss.]

There was also the fabulous pianist Alfred Brendel whom I also associate with Schubert sonatas but of course he played many other composers as well, Mozart, Beethoven, Liszt and others. An unforgettable and funny thing with Brendel in concert was his way of looking out over the audience as if to say “When everybody has stopped coughing, I will start. Even in Schubert’s sonata no.21, after the wake-up bang of the first note in the 4th movement, he makes a clear break, looks out over the audience in an almost school-masterly way and then when everything is completely silent, he resumes his playing.

To me Schubert’s sonatas Nos 20 and 21 to me are Alfred Brendel. Sometimes when you look at his face as he is playing, you are not sure if he is feeling like laughing or crying — he is so carried away by the music he is producing. This exceptional pianist makes Schubert’s sonatas his own, and I doubt if Schubert would have minded. They can just never be played or ever have been played more convincingly and moving than by this virtuoso.

Alfred Brendel is married to a wealthy and horse-loving English woman, and they have now made their home in northern London. We once watched a documentary about him and his wonderful life with his English wife on their estate and where gorgeous horses played a big part.

After all this enthusiasm, I must admit, however, that I have heard Horowitz play the 21st as well, and it was just wonderful. I remember Horowitz from Public radio WQXR (New York’s Classical Music Radio Station). Horowitz is a sorcerer. I heard him play Chopin one afternoon and I said “I like this. This is not Chopin. It’s Horowitz-Chopin.” I am not usually a fan of Chopin’s music.

We missed a concert by Murray Perahia in Lyon a few years ago. He was one of Roberto’s favorite pianists and has also become ours. So we sadly missed seeing him perform live.

We used to have a subscription to concerts at the Auditorium in Lyon, until one year we did not think the programs they offered were worth the trouble of traveling into Lyon, and we have now given up on a subscription. However, missing a concert by Murray Perahia was a thing we will have a hard time to get over.

These two soloist giants in the musical world, Fischer-Dieskau and Brendel, tower over all our memories of wonderful music in Paris.

______________

I had seen Molière’s “L’Avare” at La Comédie Française, probably in the fall of 1970, before I knew John. He saw it too, and did not like it. He said it was too dark and too gloomy. Well, I agree, it was dark and serious, but there is just the difference that I liked it and John did not. Sure it did not make me laugh, but the word comédie is used so much in French for any play that is not a tragédie, and I don’t see why you can’t make “l’Avare“, Harpagon himself, as sinister as he really was. Of course there is a happy ending, so that makes it a comedy after all. I liked the realism. I guess John didn’t.

_______________

When talking about theater in Paris, Ariane Mnouchkine may well be the theater director first coming to mind. Mnouchkine was already a legend for avant-garde theater when we arrived in Paris in 1973. She has received the Molière Award for Best Show in a Public Theatre, among other awards for best director, and, above all maybe, the International Ibsen Award, and there are even more.[11. Ariane Mnouchkine “Ariane Mnouchkine is one of the giants of theatre — she is the only female director to have ever won the international Ibsen award (in 2009), and has received honors from many countries for her achievements.” — She is an Honorary Doctor of Letters from Oxford University, awarded 18 June 2008. She holds a Chair of Artistic Creation at the Collège de France.] “The Ibsen citation declared: “to enter a Mnouchkine production is to enter another world.” In the ringing phrase of the critic Judith G Miller, she is nothing less than a “nomad of the imagination””.

Ariane Mnouchkine is a descendant of a Russian Jewish family. Her grandparents were taken to a concentration camp in Germany and gassed, but her father managed to hide from the Gestapo. After the war he became one of the most successful film producers in France. Ariane Mnouchkine was always very close to her father.

Mnouchkine founded the Parisian avant-garde stage ensemble Théâtre du Soleil in 1964, located at la Cartoucherie in le Bois de Vincennes. She was 25 years old. She had studied for one year at Oxford and after that at the Sorbonne.

She and many members of her troupe were active in what has been called “les événements de mai 1968″, in fact for many years afterwards referred to just as “les événements”. It all began as a student uprising at the Cité Universitaire, but soon spread as the students were joined by factory workers and people of all strata who “protested against capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism…” It saw “massive general strikes as well as the occupation of universities and factories across France.” (Wikipedia)

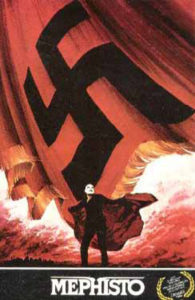

We saw the much lauded “Méphisto et le diable nazi”, in 1979. (We already knew Le Théâtre du Soleil from a previous production in the 70s, but we can not possibly remember what it was. The lack of programs takes its toll.) The play, scripted by Ariane Mnouchkine herself, is based on Klaus Mann’s novel “Mephisto — Novel of a Career” (“Mephisto — Roman einer Karriere“) the “career”referring to the highly skilled actor Gustaf Gründgens — in the novel and in Mnouchkine’s play, thinly disguised as Hendrik Höfgen.

Klaus Mann’s novel “Méphisto” was published in 1936, during the last years of the Weimar Republic. This book inspired numerous actors and theater directors who became the victims of Hitler’s immense ego and paranoia. It is easy to understand how Mnouchkine got so very fascinated with the novel.

Erika and Klaus Mann worked and traveled together for years before they moved to Berlin where Erika founded and acted with Klaus in the cabaret Die Pfeffer-Mühle (The Pepper Mill). They both became outspoken critics of National Socialism. When “the Devil”, spelled HITLER, appeared on the stage in 1933 and took power as chancellor and the Führer, Erika moved to Switzerland. Klaus Mann left for France and later moved to the Netherlands, where Mephisto was published in 1936. It was published in East Berlin only in 1956.

Many intellectuals and theater people left Germany when Hitler became the German chancellor in 1933. Thomas Mann, Klaus Mann’s father, moved to Switzerland with his family. Klaus Mann had made his home in the Netherlands, where he stayed until he decided to move to the United States in 1936. So did his father, who in fact had a strained relationship with his son over homosexuality and politics. Klaus Mann was, however, very close to his sister Erika, who was for a few years married to the famous actor Gustaf Gründgens, the model for the main character in “Mephisto”.

The Mann family were secular Jews and Gründgens found it convenient to end his association with them, an association which had, to begin with, served him quite well and had greatly enhanced his reputation. He became obsessed with his own career and he played up to Germany’s new leaders to further his personal ambitions. Gründgens / Höfgen was an opportunist — that much is clear.

Thus Gustaf Gründgens made his career within the Nazi party and became artistic director of theaters in Berlin (Berliner Staatstheater), Düsseldorf, and Hamburg. It has been very much discussed to what extent he was actually a collaborator. Was he maybe just not openly speaking out against the leaders of the “Third Reich”? In Mnouchkine’s interpretation he is the Devil himself. Judging from his enormous success, he must certainly have been ingratiating himself with the Nazi party leaders. He was, for one thing, known to have had a château-like villa. His honors in the world of theater were also there for all to see.

Whether he was indeed the ‘Devil’ can possibly remain in doubt. But in “Mephisto“, Höfgen, driven by an obsessive need for power and fame, chooses the road to hell like the ancient myth of Mephistopheles/Dr Faustus.

How is it possible to even begin to describe the fantastic ‘spectacle‘ that Ariane Mnouchkine staged with her team and which took them months to prepare. She stresses that the mise en scène is always done collectively and that it is the only way she knows how to work. Mnouchkine participates in every level of a production. In fact, we saw her helping turn all the chairs around in the intermission.

In her staging of “Mephisto”, the action takes place on two opposing stages. On one stage we saw the opponents to Nazism, Hitler and the Third Reich. These are the resistance people, grouped around the Mann family. The alter ego of Klaus Man himself, Sebastian Brückner, is the center of the action on this stage. It was also clear that the elder Brückner was Thomas Mann himself.

On the second stage we saw, in the form of a cabaret, the decadence of the finishing years of the Weimar republic and the rise of Nazism — there were the followers, the yea-sayers.

This is where we see Hendrik Höfgen (from Klaus Mann’s novel), a portrait of Gustaf Gründgens, who is Mephisto selling his soul to the devil. Höfgen’s stark white face leaves no doubt about who the Devil is.

As always, Mnouchkine’s mise en scène is flamboyant, with much motion, and, why not? — expressionism. Since I am using that term, I will just add a kind of footnote to say that I am not a great fan of German expressionist painters. I am, however, truly a fan of Mnouchkine’s fantastic, wild, colorful and constantly moving stagings and stage-sets.

_____________

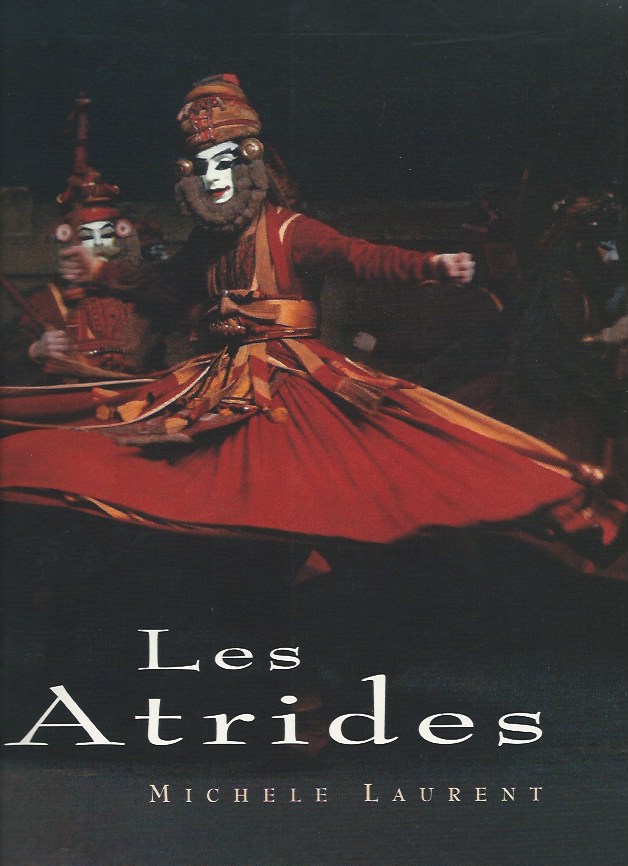

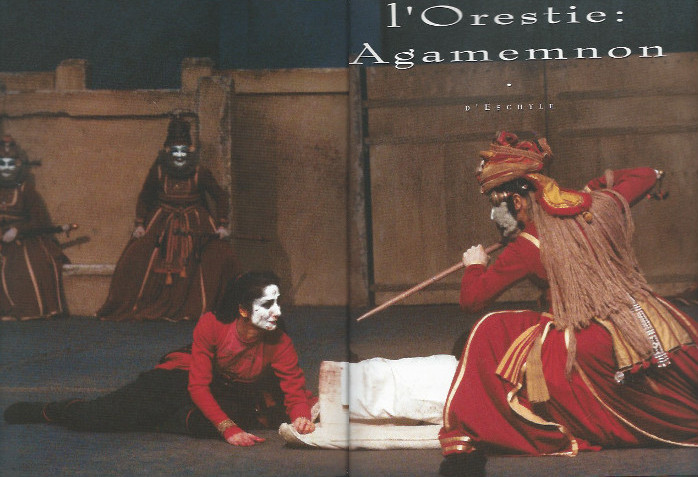

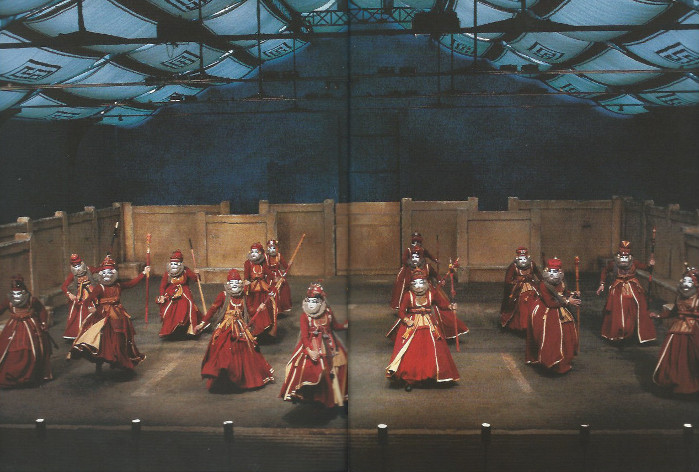

We went up to Paris from Lyon in 1991 to see the much lauded “Agamemnon”, the second in a four-play series of “Les Atreides” (Novembrer 1990- January 1993) The music was by Jean-Jacques Lemêtre, and Ariane Mnouchkine herself was one of the translators of the Greek plays.[12. Les Atrides consisted of four parts:” Iphigénie à Aulis”, translated by Jean Bollack, opened on 16 November 1990; “Agamemnon” and “Les Choéphores”, translated by Ariane Mnouchkine, opened on 24 November 1990 and 23 February 1991 respectively; and “Les Euménides”, translated by Hélène Cixous, opened on 26 May 1991].

“Agamemnon” is based on the 5th-century BC Greek play by Aeschylus. The Atreides are the descendants of Atreus, king of Mycenae in the Peloponnese, and Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus are the sons of Atreus. On the death of Atreus, Agamemnon became the king of Mycenae and Menelaus, of Sparta. The tragedy of “Agamemnon” and the curse of the Atrides is played out in Aeschylus’ play, and recreated in a most dramatic and spectacular fashion in Mnouchkine’s flamboyant ‘spectacle‘.

“The Oresteia is a trilogy of Greek tragedies written by Aeschylus in the 5th century BC, concerning the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra. The trilogy contains the murder of Clytemnestra by Orestes, the trial of Orestes, the end of the curse on the House of Atreus.”

We saw Agamemnon in 1991, and it was a most exceptional ‘spectacle’, dancers, spellbinding rhythmic music and movements and declamatory speech. Mnouchkine has learned from the theater in countries from Japan, Java, various countries in the Middle East, and the influence is visible in this four-play series, “Les Atrides”, more than ever. Flamboyant colors, music and rhythm are the thread that makes this an artistic unit. The declamatory speech and the wildly painted faces are of course designed to recreate the speech and masks of ancient Greek theater.

Dancers in “Agamemnon”, in which play Clytemnestra kills Agamemnon for revenge of his killing Iphigenia, their daughter — photo from booklet.

_________________

Le Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord (Festival WorldStock 2017

While on the subject of avant-garde Paris theater, aside from Ariane Mnouchkine, there is also another major creator of those spectacles who must not be left unmentioned. Peter Brook had his Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in the 10th arrondissement, verging on the 18th, just west of the Gare du Nord. He had created this haven for superb theater productions from a totally run-down theater building, that very few people, maybe just one woman, ever knew existed — behind a façade of an ordinary apartment building and seemingly left to decay.

The Bouffes du Nord theater was built in 1876, but it was forgotten and had fallen into total disrepair So it had to be quite thoroughly restored before it re-opened in 1974 under the direction of Peter Brook and Micheline Rozan who had managed to get funds for the restoration, when the ministry refused to participate in. [13. “Peter Brook et Micheline Rozan, fondateurs du Centre International de Créations Théâtrales, se souviennent de ce bâtiment délabré qu’est le Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord. Grâce à l’appui financier du Festival d’Automne, que dirige Michel Guy, ils le font restaurer avec une intelligence et un goût remarquables. … Pourtant, nous remarquâmes sur le mur un bout de carton qui bouchait vaguement un trou. Nous le retirâmes, nous nous frayâmes un chemin à travers un tunnel poussiéreux, pour soudain nous redresser et découvrir, délabrées, carbonisées, ruinées par la pluie, grêlées, et pourtant nobles, humaines, lumineuses, à couper le souffle : les Bouffes du Nord.”– 1974, la réouverture du Théâtre par Peter Brook ]

We were there several times, but I doubt if there even were any programs. I remember one of Peter Brook’s actors that I didn’t like, but who was in every play Peter Brook staged. I found him as rigid as a fire poker, and he had a strange accent when speaking French, but there he was, every time.

Peter Brook’s productions were always remarkable but still I do not remember too well what plays we saw at the Bouffes du Nord. Bizarre. And no programs to help my fading memory along. However, the mise en scène and the acting were always mesmerizing, and the way we were always sitting right next to the actors greatly enhanced the feeling of being in the play. That’s what I particularly love about theater. Too bad that I remember so badly what plays we saw there. Les Bouffes du Nord is definitely a very exceptional avant-garde theater.

One time I remember well was when we went there with Arne and a childhood friend of his, Claes Hoogland, who was a producer and theater critic at Sveriges radio (Swedish radio). Claes was quite a bit younger than Arne, but their parents were close friends, and so they got to know each other very early on in their lives. They were also both connected to the theater..

The first time I got to know Claes Hoogland was when we passed through Göteborg in 1949 on our way to Bohuslän, the west coast, on our summer vacation, Arne had arranged with Claes that he would show us Göteborgs Stadsteater behind the stage. Claes had a position as secretary at Göteborg City Theater at the time.

We met Claes again at his parents’ New Year’s party a couple of years after that (evening gowns and all; mine was self-made, not too bad) at their magnificent apartment on Östermalm in Stockholm. Tante Gerda was there of course, since she was the real link to Claes’ parents. Both events have become part of fun memories from my early youth.

The next time I saw Claes Hoogland would be in the late seventies in Paris. He and his wife had come from Stockholm to Paris just to see les Bouffes du Nord, which they probably knew already and this Shakespeare play. We would of course have read the play before seeing it. The play was “Mesure pour Mesure” — (“Measure for Measure”), a black comedy, and the year was1978. It was an excellent performance, and Claes and his wife had not come for nothing. Peter Brook himself had directed the play of course.

So we were at the theater with Arne, Claes and his wife. We were sitting on the hard benches without backs in the front of the theater, and in fact I don’t know personally of any other seats there. There are somewhat more comfortable seats in the back. Also it looks as if they have put chairs on the seats in the three balconies. I remember well that Claes and his wife were sitting behind the three of us, Arne, John and me,

We saw “The Threepenny Opera”, (“L’Opéra de quat’ sous”) in 1979 by a German theater company, Skarabäus. Since it was a German performance, it was more exactly “Die Dreigroschenoper” in this case. This beggars’ opera is the play by Bertold Brecht and Kurt Weill which has followed me through my life. It began with the wonderful production at Malmö Stadsteater in 1946. (I mention this in my chapter about Mamaroneck High School theater and of course in the chapter about my youth and the theater) Here it was performed in German, the language I prefer for this play. Singspiel I guess it could be called.

This play about great poverty and gangsters — Mr Peachum, the king of beggars and Mackie Messer (Mack the Knife), the king of crime — is certainly Brecht’s message to the bourgeois community that another world exists, which we would do well to be aware of. It was a lively, funny and moving performance, where, for instance, two women compete for Mackie’s love, one being Peachum’s daughter, Polly, and the other one the daughter of the police chief. “The opera of extreme poverty” (“l’opéra de la misère”), says the director, Hans Peter Cloos.

In November 1981there was “La tragédie de Carmen” at the Bouffes-du-Nord, byPeter Brook — Jean-Claude Carrière and Marius Constant having melted down the original “opera buffa” into one hour. It can safely be said however that nothing was lost of Mérimé’s moving story or of Bizet’s wonderul and rousing music. However, this was a very different “Carmen” from what you usually see on the big stages all over the world.

John and I had seen “Carmen”at the Metropolitan Opera with the great mezzo Marilyn Horne, an excellent and very passionate production, but this production at les Bouffes du Nord was something very different. It was more like a realistic and contemporary story and it was immensely moving. Carmen was sung beautifully by Hélène Delavault; Howard Hensel interpreted Don José. John remembers the name of Hélène Delavault as Carmen. In fact, to be really truthful here, we are not quite sure that we saw Carmen at the theater. We might actually have seen it on television. I collected all my theater programs since my years in Stockholm, but I don’t have a single one from les Bouffes du Nord, which seems to tell me that there weren’t any programs.

Peter Brook’s “La tragédie de Carmen” was made into three movies in 1983, with three different cats.

_______________

We went to le Théâtre de la ville at the Place du Châtelet several times. It was once called Théâtre de Sarah Bernhardt, who was said to have been one of the greatest actresses ever.[14. More about Sarah Bernhardt in Chapter 24 – Arne and Drottningholm Theater] She is even known to have played “Hamlet“. I remember well seeing Théâtre de Sarah Bernhard inscribed in big letters over the entrance to the theater. The name was changed in 1967, when it became Le Théâtre de la Ville.

There was “La Guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu” (“The Trojan War Will Not Take Place”) by Jean Giraudoux in 1975. Director (metteur en scène) was Jean Mercure, actor and theater director who was the founder and the director of Le théâtre de la Ville from 1967 to 1985.

In this play Giraudoux uses the war in Troy, which ultimately does take place, as a symbol for his stark criticism of the diplomats and national leaders who could not or would not avoid World War I. So the tragic myth of the ten-year Trojan war is the framework, but the message is clear. We know what Giraudoux is really talking about. And very likely, in 1935, when the play was written, Giraudoux could already see what World War I was going to lead up to, since Hitler, after becoming the chancellor in 1933, did not make a great secret of his aggressive plans and actions.

In February 1981 we saw “Le canard sauvage”, (“The Wild Duck”) once again at LeThéâtre de la Ville, metteur en scène – Lucian Pintilie. This is the wonderfully gripping and tragic play by Henrik Ibsen. In Norwegian and in Swedish it is called “Vildanden“, which I find so much more beautiful as a title. It does not bring to mind a dish served in a restaurant.

Hedvig, the photographer Hjalmar Ekdal’s daughter, kills herself in the end because she believes her father doesn’t love her any more. She does not know that Hjalmar has found out that he is not the real father of his much beloved daughter Hedvig.. His wife, Gina, once upon a time had an affair with the rich wholesale dealer, Gregers Werle.

I saw this deeply moving play in a magnificent production at the “Royal Dramatic Theater” in Stockholm in 1955, when I was invited by my childhood friend Britt, who comes back several times in these Sketches.. (See Chapter 10 — – Stockholm theater). Even though I don’t like the sound of the title in French or in English, I admit that it was a very good performance of this heartrending play. However, the Stockholm production, directed by the masterful Alf Sjöberg, who has gone down to Swedish theater history (quoting myself from Chapter 10), and which I actually saw twice, the second time I and my husband Roland were invited by Arne and Mother, when the play was reproduced a few years later.

The one play I remember the best from Le théâtre de la Ville is “Peer Gynt”, also by Henrik Ibsen — in October1981, mise en scène by the great theater and opera director, Patrice Chéreau. It was basically a fine performance but there was one quite important thing that irritated me and John very much. Chéreau had made Gérard Desarthe who played Peer do odd things with his head, as if he was feeble-minded or half mad. And that, I think I can say with certainty, was not Ibsen’s intention in his drawing-up of this character. Peer Gynt is neither crazy or feeble-minded.

This poetic and philosophical play is extremely difficult to stage because of its mixture of the fantastic, the poetic and realism. Patrice Chéreau had chosen to include all of Peer’s travels and misfortunes and the play was performed in two parts of three and a half hours on two different evenings, which we found a bit exaggerated.

Peer does not distinguish between right and wrong, because Böjgen (the “Boyg”) at the beginning of the play has persuaded him to avoid all problems in his life by “going udenom” that is outside, or more exactly here: around. He cares about nobody but himself. Evidently, there have been many parallels drawn between Ibsen’s “Boyg” and Goethe’s Mephistopheles — or Klauss Mann’s Mephisto for that matter. The great difference is that Peer is saved in the end by Solveig, the love of his youth.

In my class in Gymnasium we had to read parts of an abridged version of Peer Gynt in Norwegian and I was extremely impressed by the notion of Böjgen who blocks the path for Peer as a young boy and tells him to “go udenom”; that is not facing up to any real moral dilemmas, follow the easy path of complete selfishness. He travels around the world without ever finding his real self. In the very end, after a great number of adventures and misfortunes, when he is trying to become an emperor, after almost drowning in a shipwreck, he gets back to the hut in the woods where he started out on his wild and self-aggrandizing adventures. He hears Solveig singing and he realizes where his real empire is. He is now an old man and he is saved by the love of his youth.

Quoting myself from “Chapter 4 — My youth and the theater“, about the masterful production of Peer Gynt by Ingmar Bergman in 1957 at Malmö Stadsteater, a 5-hour performance: “I will never forget Naima Wifstrand, when she is disillusioned with her son, Peer. She is sitting on a rock, peeling an onion, one layer after the other until there is nothing left. She is peeling the layers of identity of her son. There is no core, nothing at all. This is very likely one of the most famous symbols in theater history and it is also probably one of the best-known Scandinavian theater plays ever written.”