Chapter 18 (Part 1) – Mamaroneck High School and friends

Cézanne, nature morte — one of the beautiful reproductions I had on the walls of my classroom.

It is now 1967 and I have changed schools. And I am now Mrs Phillips. Husband Allyn is my colleague here. I get a better salary, a better standard overall, and a school situated right on the old Boston Post Road, with Long Island Sound a stone’s throw away, right next to my beloved sailing waters.

It was a whiff of the past. You could almost imagine hearing the hooves of Paul Revere’s horse as he hastened to spread the “alarm” of The Somerset, the British man-of-war, being anchored in the Boston harbor.

Better students? Well, they couldn’t very well be better than my fabulous junior French 4 class in Mount Vernon High School, which will go down in history through these memoirs. And the wonderful Get-well-card they sent me when I was in the hospital with a complicated elbow fracture. But there were quite a few students in Mamaroneck High School whom I still remember for various reasons.

Maybe first of all there was Christine. She sat in the back of my class trying to hide because she never did her homework. However, whenever there was a test, she did very well. On Homecoming Day the year after she had graduated, she came to see me in my classroom. The school had two major buildings, one on Palmer Avenue and the one where I was the last couple of years, on the old Boston Post Road. The two were connected by a long corridor so the students got a lot of exercise changing classes and always had a good excuse for being late for class, even if the reality was a smoke in the boys’ room.

Christine was sitting talking to me for quite a while after school that day and she said she had come only to see me and the music teacher, Neil Slater. She told me she was studying political science at Boston University, taking evening classes, while she worked during the day to support herself. One of her teachers was Howard Zinn. No less. I found it quite surprising that she worked while being a student since she came from a wealthy family. She told me later that she despised her father and would not accept any money from him. Great kid!

She gave me a book before we left for Paris – “Teaching as a Subversive Activity” by Neil Postman that I very much enjoyed reading. I’m sure Howard Zinn had got through to her.

Marijuana — pot — was beginning to appear a little all over, even in school, and smart skirts and shirts for the girls were exchanged for jeans and T-shirts or sloppy sweaters. It took a while though before the principal, Joe Downey, had to finally permit the wearing of jeans for female teachers. The Times They Are a-Changin’. Oh, my idol, Bob Dylan.

More about Christine later on, as she parachuted into my life when John and I were living in Paris.

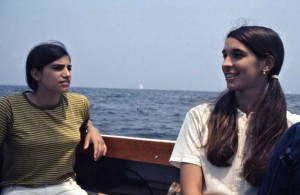

There was my dear and young friend Nora, a sophomore in my French 2 class. Christine was a young woman, Nora was a young girl with long dark hair. She and her friend Rita helped John and me pack our hundreds of books when we got ready to move to Paris.

Nora and her friend Rita on the sailing trip to change marinas for Kijé.

They also went out sailing with me or with us a day when we moved my Rhodes 19 from a cheap marina in Pelham (Allyn’s choice) to the New Rochelle marina, which was of course much closer. John doesn’t like sailing, but he goes along of course and he took the pictures. He also takes care of the motor when it’s needed for moving in and out of marinas.

Many years later, when we already lived in Genas, I visited my very special friend Norma in Brooklyn, my colleague from Mount Vernon High School. John had gone to a meeting at his old lab, Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, while I spent the time with Norma first, and then with my also very dear friend Annie from Ecole Centrale de Paris.

Annie had married Louis-Henri, a French “grande école” engineer. They first lived in Grenoble where she had her first child. After I had my ski accident in 1981, she came to see me every day at the hospital Grenoble Sud when she was highly pregnant. It was wonderful since it was a long way for John to drive to Grenoble from Alpe d’Huez where I had my accident – on the first day of skiing, typically. Later, Annie and Louis-Henri moved to Appleton, New Jersey, probably because there was more of a future for Louis-Henri in the U.S. It seems to have been a wise move. Annie was closer to her family, in upstate New York, and Louis-Henri made an excellent career, mainly as a contractor.

During my visit to Norma, who was now named Fine and no more Jochsberger, I remember lying on Norma’s bed and having a long chat with Nora. She said “You sound so American”, surprised that I hadn’t changed after a few years in Paris. Nora greatly admired my very good friend, Girv Milligan, who was the special-education teacher at our high school. I never attended one of his classes, but I am sure Nora admired his way of dealing with these handicapped kids. So she decided that was what she wanted to do with her life. I learned via the Internet that she got a Ph.D. and that she is the assistant principal of Larchmont middle school. So one day I tried to get through to her via email, and through a colleague of hers I succeeded. I was very happy to get back in touch with Nora and pleased to find out that she is very active, but seriously considering leaving teaching for some other activity. So we’ll see what happens.

There were two French girls whom I remember well. One of them, Joëlle, didn’t speak French perfectly well and it was decided that she should be in a French class, probably level 3. I remember how she once said “J’ai tombé” and I was very surprised. I said “But Joëlle, you don’t say J’ai tombé, but Je suis tombée”. I was surprised because I thought that should be obvious to a French girl, even if she was young. However, the poor girl had been out of luck with her schooling. Her father owned an excellent restaurant in Larchmont, but before that he had a restaurant in Colombia and the poor kid had first had to learn to speak Spanish and go to a Spanish speaking school. Then the family left Colombia for Larchmont — for political reasons or not one will never know. Joëlle now had to learn English as well as improve her own native language. But her father made the best canard à l’orange John and I have ever eaten.

Anne was the other French girl who became my friend and she was not in any French class at all since she didn’t need it. Her father had temporarily been stationed in the New York area by IBM and they had settled in Larchmont, which was an up-scale residential town. She would come to my room just for the pleasure of speaking French. She said I was the only French teacher who spoke the way French people speak. Well, we became friends and one day when I asked her to please call me Siv and not Mrs. Phillips, she replied “Well, if you promise to say tu and not vous” (tutoyer rather than vouvoyer). Done. Since then I have learned that grownups don’t say vous to a 15 or 16-year-old, but at the time there were still things I had to learn about in French customs and culture.

Since I moved to Paris for a year in 1970, at the same time as her family moved back from Larchmont to the posh western suburb of Paris, Vaucresson, where their home was, they once invited me over for dinner. Her mother picked me up in her little Fiat on the Champs-Elysées in front of Fauchon, and poor Anne, it turned out, was all unhappy because she had a terribly swollen cheek from a tooth problem, extraction of an early wisdom tooth or some such thing. Her mother was very welcoming and pleasant. I guess she was grateful to me for having in a way cheered things up for her daughter while they lived in Larchmont. I also often drove her home to their house in Larchmont after school and chatting.

We had a nice dinner, and it was altogether a very pleasant evening. Also, I don’t believe I have ever seen a more beautiful apartment. At one point when I was alone in the living room, I happened to get up and go over to the big windows and I still remember the curtains that were works of art.

I have left out many students I remember well, but I will mention Laura Solow, the excellent musician who brought her guitar to class one day on my request and gave us a wonderful mini-concert of her virtuoso guitar playing. She also played the cello in a school performance of one of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. She told me about the concert and asked me if I would come so of course I did. The only problem was that Allyn and I were separated in the spring of 1970, but once again I asked him if he would come along with me. He came. I know she used to play with my colleague and friend Al Levinson’s older son who played the piano and Laura the cello, I guess. Al told me about that much later on in Paris.

There was also Debbie Margolin, a very smart young girl who was Laura’s great buddy. This smart girl turned out to be a writer and performer of theater plays, performing in New York City and north and south of the City. She is also a “Professor in the Practice of Theater and Performance Studies” at Yale University, which impressed me very much. She is now Deb, no more Debbie, by the way. I got in touch with her and three more girls from that class via Facebook.

_______________

There were also some remarkable teachers who should be mentioned. My very good friend, Janet Rogowsky, comes first among them. Janet taught Russian and French, and she and I became quite close after Allyn and I separated around New Year’s 1970. Being quite a bit older than I, she took me under her wing. Janet saved me when she suggested that I should take a year off from my high school where I now had tenure, go to Paris, get a job and find someone “better suited to you, while you are still young and attractive.” Those were her words.

Janet was definitely not one of the many women who fell for Allyn’s charming smile. She did not like Allyn. I did as Janet had recommended — no, had told me to do.

Trough an enormously lucky turn of events, I found an English teaching job at l’Université de Paris Sud in Orsay, south of Pars. I met John in January after a fairly dull fall semester. I was now considered as a native English speaker and that was what brought about my lucky breaks, first in 1970 and again in 1973 when John and I came back to Paris as a newly married couple. This lucky event led me to where I am now, sitting in my comfortable study upstairs in our beautiful home with three wonderful animals. John’s and my life has improved as the years went by, and we are now considering ourselves as a very privileged elderly couple with a home that is a paradise, especially on sunny days when we can leave the veranda doors open to our yard and the animals can move in and out. The strange thing is that I don’t actually feel all that “elderly”, even though I know well that I am.

Rarely did a Jewish woman in the United States have as much to tell the world as Janet did. I have very recently learned from a former student of mine, Nick Holst, who magically found me on the Internet in spite of my name change, that Janet has in fact written her auto-biography, her “testimony”.

The following is her story, which can be found at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC.[1. Testimony of Janet Rogowsky, Collection of testimonies, Acc.1996.A.431, USHMM – Also: Ostrog – A Metropolis of the People of Israel]

My wonderful colleague and friend, Janet Rogowsky, née Ajzenberg (Eisenberg), probably 16 years old.

Janet was born in a city called Ostrog in eastern Poland, bordering on Ukraine and formerly having been part of Ukraine, where Jews had been settling for hundreds of years. At the beginning of the second world war, two thirds of the population of the town were Jewish. However, I now realize that Janet only told me a very little part of the truth. She told me that they, implying her family, had escaped the Holocaust by living as Christians. They had been careful not to overdo anything, as many people did, by wearing very visible crosses around their necks and behaving too ostentatiously like Christians. She also once told me that she had been married previously to a young Polish artist (who, as I later found out, was named Feliks Puterman) and that they had first lived in Paris.

The truth of what she experienced during the war was far more horrible than what she led me to believe, and actually most of her family died in the Shoah. One sister, Anya, was the only survivor besides Janet herself and she and her husband and two small children finally joined Janet and Feliks in New York City. What she herself and Anya had gone through before that was told in her testimony. It was heartbreaking reading.

After the Russians had “liberated” Poland from the Nazis in 1944, she moved back from her several-year-long “hiding” in Germany, where she had been working, partly as a tutor to a 12-year-old boy whose native language was Polish, and partly as a domestic. She presented herself as a Polish-Christian young girl after having miraculously managed to cross the border into Germany, and she was treated very well. For the first time after the beginning of the war she was getting enough to eat. even though rations were very limited during the war. She was not treated as an outcast and she had a place to sleep.

Back in Poland in 1944, she tried very hard to find out if any of her family members had survived the Holocaust. She first went to Ostrog where she found only ruins and rubble. She avoided going to see their once so beautiful home, since she was told that it had been completely changed, even though it had in fact survived the horrible destruction of the town.

In continuing her search for her family, she went to Warsaw where she helped found a home for war-damaged Jewish children. The deportation of Jews had left a great number of orphans. They had been dropped from the wagons destined for concentration camps or had otherwise been abandoned by their parents, in the hope that they might be given a chance to survive.

The Warsaw ghetto was created by the Germans in 1940 and in 1942 100,000 Jews had died from hunger or sickness. In addition to this, 300,000 were deported to Treblinka where they died in the gas chambers. Warsaw was in ruins at the end of the war and the Jewish ghetto after the Jewish uprising in April-May 1943 had been thoroughly emptied and destroyed. Practically all the inhabitants were murdered.

Janet cared for these severely disturbed children, who trusted no one at first and who knew of nothing other than stealing food when they were famished. However, now under careful treatment they gained in self-confidence and trust in their helpers and each other. This was where she actually employed Feliks, her future husband. He showed up one day after he had just a couple of months earlier been liberated by the Allies from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, on May 3, 1945. He weighed 88 lbs. when he was freed. He now wanted to help survivors, and Janet and he together cared for the children and tried to get them to trust other people. Feliks was an artist and possibly that was the reason why he had survived in the concentration camp. He was useful in painting barracks. Before the war he had lived in Paris and as a painter he had already exhibited some of his work.

One thing that impressed me very particularly in Janet’s testimony was how she said she pitied the German soldiers who had to carry out orders to kill and torture. They drank themselves into a stupor in the evenings, and how else, she says, would they be able to carry out these inhuman orders? It takes a big heart to even forgive your enemy and torturer when you are yourself in mortal danger every minute.

After much hesitation because of Felik and his career as a painter in Paris, she traveled to New York to see her three uncles who lived in Brooklyn and Long Island. They convinced her to stay, and after a while Feliks joined her and became her first husband. He died of a stroke in 1955 while still young. Janet was devastated.

Janet developed a sense of caring for others which she carried on as a teacher. She studied at Columbia University after she had worked very hard on learning English, her new language. She met David in our high school, and, as she says, her friends realized that there was a new spark in her eyes. Her students loved her, and when she and David got engaged they saw her engagement ring and went wild with excitement.

I was also going to be one of those people that she cared for in her great generosity of feelings. I will forever be grateful to her for suggesting that I take a year off from Mamaroneck High School, since I had just got my tenure as a French teacher. This was when she suggested to me to take a year off and go to Paris. Actually, she didn’t just suggest, she told me to do so – while I was still young, as she said. She did not think much of Allyn.

______________________

I joined Janet and usually quite a few of her students on theater trips to New York City in the spring of 1970. We saw Le Tréteau de Paris, the wonderful French touring company, at the “Barbizon Plaza Theatre” on Central Park South, playing “Lettre morte” by Robert Pinget and, another time, three short plays by Eugène Ionesco, “La jeune fille à marier”, “La lacune” and “Les chaises”. I already knew Ionesco from Paris of course, but just the two plays that played for decades close to Place Saint Michel in the 5th arrondissement at le “Théâtre de la Huchette”, “La Leçon” and “La cantatrice chauve”, starting in February 1957. I had also read some other plays of his. A few years later I read “Le roi se meurt” after John recommended it and I loved it. However, when we saw it in Lyon much later in 1988, it was an uninspiring performance with Annie Girardot and we were very disappointed. She was usually very good, so we were wondering what had gone wrong.

The most unforgettable play I saw with Janet was certainly Samuel Beckett’s “Oh les beaux jours” (“Happy Days”) with Madeleine Renaud as Winnie embedded up to her waist in a low mound of sand and prattling unceasingly about meaningless things. Her husband Willie is mostly invisible and silent. Again, it was a performance by Le Tréteau de Paris. (1970) [3. Oh les beaux jours (Happy Days) with Madeleine Renaud, mise-en-scène Roger Blin]

“Oh les beaux jours” to me is Madeleine Renaud, and John and I later saw her performing it in Paris too. That was in 1981, at the “leThéâtre du Rond-Point”, off les Champs-Elysées; the theater at that time was owned and run by Madeleine Renaud and her husband Jean-Louis Barrault. It was the same mise-en-scène by Roger Blin as in 1971 in NYC. How can anyone forget Madeleine Renaud, half buried in sand, when she is looking at her toothbrush and reading with some difficulty ‘”garanti véritable… pur… porc” . It probably sounds banal, but it is spellbinding the way she says it. I can still hear her reading those tiny-printed words on her toothbrush.

Janet and I also saw her husband, Jean-Louis Barrault, also a superb actor, in “Rabelais”, in May 1970 at “New York City Center”, south of Central Park. The play was written by Barrault and consisted of excerpts from Rabelais’ writings. It was an impressive production, totally wild and Rabelais-ish. I just minded Jean-Louis Barrault in one scene when, totally against theater proper mores, he upstaged the actors who were performing the main plot at center-stage while Barrault did comic grimaces upstage. Of course he was funny, but it is not good acting manners to draw attention to oneself when co-actors are playing a scene on center stage. Jean-Louis Barrault, the great star, one of whose first movies that put him on the map was “Drôle de drame”, the immortal movie by Marcel Carné from 1937.

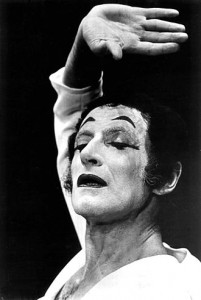

Later on, in the spring of 1973, John and I with Janet and several of her students saw the famous pantomime artist, Marcel Marceau at the “New York City Center” on 55th Street. It was amazing. It was hard to believe how you could fairly see him open the door that wasn’t into a room that wasn’t and touching the walls firmly that were not there. That was the pantomime that I still remember, but he was altogether, in all his various skits, unbelievably imaginative and masterful.

We saw Janet and David a couple of times at least after 1973 in Paris. It was always a great pleasure to see them again.

_______________________

Sylvia Goldfrank was another French teacher who became my friend and whom we also saw several times later on in Paris, together with her husband Max, whom she referred to as ‘my handsome husband’. And indeed he was that. Sylvia was a character. Janet was probably just as much of an intellectual, even if she didn’t display her erudition in the lively way that Sylvia did. Sylvia was funny though. She would say for instance: “I love the way Macbeth says “Hell is muuurky” and as she acted it out, you could practically see hell opening up. Her parting words to me were “What is Sylvia going to do without Siv? ” I was quite moved.

There were other teachers whom we saw later on in Paris. The history teacher, Madge Rosenbaum, who had by then retired, had a house in Dordogne, one of the greenest and most beautiful regions of France, east of Bordeaux. She spent half the year in Larchmont and the other half in Dordogne. She traveled by ocean-liner because she would always come over with half a house-full of stuff, including toilet paper.

She became a good friend until we visited her in her wonderful house in Dordogne. She graciously invited us to come and visit her there but, stupidly, we had not made sure if our pets at the time, wonderful Puppy, a German Shepherd, and equally wonderful cat, Mélisande, were also welcome to her house. Obviously it became quite a shock to her when we showed up with our two animals. It turned out that even though we kept Mélisande closed up in a room and Puppy was outdoors all day, she was still very bothered by our animals since she was allergic to both cats and dogs.

We did have a lot of fun though when we found fresh dill in flower in her vegetable patch. That is just what it takes to cook crayfish the Swedish way, and I was delighted. We bought live crayfish at the market and I cooked them in beer mixed with water, lots of dill crowns and of course a lot of salt, and we let them sit outdoors to cool off until the following day. That’s how the crayfish soaks up the taste of the dill, the salt and the beer. We had however made another boo-boo, since it had never occurred to us that Madge would like Swedish snaps. Snaps is of course a must to go with crayfish eating. We were saved anyway by some vodka that Madge happened to have in the house. The crayfish were delicious and we had a good time in spite of it all.

It had still not become quite clear to us that Madge was allergic to cats and dogs, and when we invited her to our apartment in Paris later on, we found out that she was miserable because of her allergies. Once again later on we took her out to a very good Chinese restaurant, but after that our socializing sort of simmered out.

One thing though that really impressed me was how Madge had seen the Ballets Russes in Monte Carlo with her father a long long time ago. It must have been the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo in the 1930s, after the death of Diaghilev. More about this in Chapter 22 (Part 1).

Another friend, Gwen Kelly, was a young French teacher about my own age who, funnily enough, had kept her British accent even though she grew up in California. She didn’t like her first name, so she was always called Kelly. She was a happy young woman and we never understood why she didn’t have a male friend. I do think that was a matter of disappointment and sadness for her.

Allyn and I once asked her if she’d like to go down the rapids with us on the Delaware River, ‘shooting the rapids’, as the expression goes, even though the rapids were not extremely rapid at that place in the river. We put our canoe in the water at Hancock New York and went south to Port Jervis. This time we stopped in a bar on the way, as Allyn and I would quite often do, usually to have a Tom Collins. I remember clearly a very German pub on the Pennsylvania side where they had German decorations, some with inscriptions in German. That’s when I realized that the Pennsylvania Dutch are not at all Dutch but Deutsch. Just a misunderstanding by the Anglophone people in their new country.

This time it wasn’t on the German side of the river, but in a fairly lackluster bar on the New York side. I surprised Kelly confiding in Allyn, when I was out for a moment, very likely telling him about her disappointment in not having a male friend. Allyn was a charmer and I do believe that quite a few women had a crush on him. But I don’t really think Kelly was sending out tentacles to hook Allyn, even for a brief affair.

I might add here that when I returned from my year of teaching English at Paris University, I found a totally metamorphosed former husband, and very much for the worse in my view. His nice looks were all gone under his long seemingly never-brushed hair and a wild beard. He had also totally accepted his role as a philanderer. He told me I had to pay for the divorce since he had paid for the separation, and he was never again going to get married anyway, I said Ha! He only got married twice again, four times in all. Instead of the nice suits we had bought for him, since the suits he had been wearing in Sweden were far too big for him because of his 6 feet+ height and skinny frame. Those suits had now been exchanged for a hunter’s type jacket and t-shirt under that. The rest was in the same style. He looked seedy, as a colleague of mine warned me before I had even seen him on my return to Mamaroneck High School.

Teachers in those days wore suits and a tie or something similar. However, while I was away a new school within the school, SWAS, had started. They had their separate premises on the ground floor on Baston Post Road, and Allyn was the English teacher. I don’t even remember if the other SWAS teachers were dressed in the same coming-in-from-the-wilderness fashion as my former husband, but the students probably were. The run-down style must have seemed attractive to some people, including women. Apart from the way of dressing, I don’t really know how the running of SWAS was different from our “normal” classes. I assume that there was more “freedom” of speech and less discipline. Since I was never a disciplinarian I can’t really imagine what the changes might have been.

I have since understood that for men like Allyn a good-looking woman has but to have a cute smile and eyes gleaming of adoration, and he is conquered. As soon as the eyes gleaming of adoration are no more, he will look for a renewed version of the adoring eyes, and if the man is Allyn he will find them.

Back to Kelly though. She had done quite a bit of skiing in California, which surprised me since in my great ignorance of my new country at that time, I didn’t even know that people do a lot of skiing in California. She once came with us to Vermont when quite a few of us from school went to Stratton and Bromley mountains in southern Vermont to do the most fun skiing I have ever done. I remember very well one particular time when there had been snowstorms in our area and on the radio they claimed that all the entries and exits from the thruway up to Vermont were closed. We said “Let’s try anyway”, and we did get both on and off, as did everyone else, and we had a jolly little group at a very modest hotel in Stratton.

Especially on Bromley Mountain I found a long ski trail that was just perfect for me, and I was exhilarated by being able to pass other skiers, crying Passing left and Passing right. I believe that was the time when it was so cold that we had to wear face masks. Up at the top of the mountain it was obviously a lot colder than down below.

However, the most memorable skiing I’ve ever done was at Flaine, the up-and-coming French ski resort in the French Alps. I was there all by myself in the early winter of 1971, just before I met John. Since Flaine was in those days just in the beginning stages as a ski resort, it had only three hotels, and I was probably staying in the medium-proced one. As I took the ski lift up to the very top of Flaine, I had a breathtaking view of Mont Blanc under the sun. The weather was crisp and clear and seeing this gorgeous mountain so close up was unforgettable. That’s also where I learned to ski over moguls, using the little humps to turn on. During lunch in the ski station I got to know a young man from outside Geneva, where he owned a café-restaurant. He was a good skier and he got me up on the trail with the moguls. I never thought I would manage, but I did, under his supervision.

Kelly was another friend and former colleague whom John and I saw in Paris too, still without a boyfriend. I remember her having dinner with us in our little apartment in the 13th arrondissement in Paris. Apartments are terribly expensive in Paris of course, and were in those days too, so we only had a smallish apartment. We usually had our meals in the kitchen, and only for very special occasions did we eat in a corner of the living room, where we could set a nice dinner table. We only got more space when we moved to the Lyon area, in fact had to move to Lyon because of John’s job with the CNRS (Centre National de Recherche Scientifique), their computing center which served all the CNRS physics labs in France (IN2P3) being decentralized to Lyon. We then bought a fairly small house in a pleasant suburb of Lyon. We later had the house enlarged, in fact twice enlarged, so it’s now wonderfully comfortable.

But the saddest Mamaroneck story was the terrible drama of Eve and Al Levinson. Al was an English teacher and a writer, and he also taught creative writing at New York University in downtown Manhattan once a week. He was a handsome and likeable man, and he seemed to be one of the true intellectuals in the English department. But it was Eve who was my very good friend. In the days when I was working in the Palmer Avenue building, I would often have lunch with Eve, who was a regular substitute for any of the English teachers. She was one of those warm and intelligent women whom you like right away, without any reservation. She gave me many good tips about good readings and got me to know writers that I may never have discovered if it hadn’t been for her.

Eve also recommended Alan Sillitoe’s wonderful book “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning“, a book that became one of my very favorites. Like so many other favorite books of mine, I read it with a class later on in my engineering school in Paris, a ‘grande école’, l’Ecole Centrale de Paris. I was so enthusiastic that I do believe my students ended up liking it just about as much as I did myself. It is wonderfully suited for reading with a class since each chapter more or less reads like a short story.

Also by Sillitoe’s there is his wonderful short novel “The Loneliness of a Long-distance Runner”. I loved it just as much as “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning“, but I didn’t think it was quite as well suited for reading with a class.

One more writer recommended to me by Eve was Brendan Behan and his best-known book, Borstal Boy.[2. Borstal Boy – Wikipedia: “From a technical standpoint, the novel is chiefly notable for the art with which it captures the lively dialogue of the Borstal inmates, with all the many subtly distinctive accents from the variety of the British Isles intact on the page. Ultimately, Behan demonstrated by his skillful dialogue that working class Irish Catholics and English Protestants actually had more in common with one another across class barriers than they had supposed, and that alleged barriers of religion and ethnicity were merely superficial and imposed by a fearful middle class.] I loved the book for its genuine style and its total lack of hypocrisy. It was as true to life as it could possibly be, and it was also dealing with a subject that is very important to me, which is the conflict between Irish Catholics and the northern Protestants, the seemingly endless war situation that we all wish could come to a lasting end. When we were in Ireland in 1997, we did get into Northern Ireland, but we actually skipped Belfast. The horrible huge posters that assure you that you are saved if God loves you were a thing that put horror in our souls.

It is so rare to find a person that you can sympathize with immediately and in such an unquestioning way. I always loved to see Eve when I got to the lunch room, and she got to be a real friend.

The language department was moved over to the Boston Post Road building after some time, and unfortunately I more or less lost touch with Eve. I still miss her today.

But something happened that killed her. Later in Paris, after I had heard already that she had died, Al, her husband, told me that she had fallen off the roof of their house. This sounds very strange to me. What on earth would Eve be doing on the roof of their house? She was anything but a hysterical kind of woman.

I will of course never know what really happened, but the surprising thing is that Al, not too late after that horrible event, announced to us that he was arriving in Paris with his new wife, who was really just a young girl. This was in the mid-seventies. She was French and she came from Bretagne. She had nothing remarkable about her, and I can’t even remember her name. However, she was in with the Monty Python gang, and that is how Al had come to know her.

Al had, some time after I left the U.S., become friendly with Michael Palin, of Monty Python fame. Al’s first two books are the basically autobiographic saga of a Jewish family who had immigrated from Russia, and it was first published by the Monty Python publishing company, Signford. Later on, in 1984, Oracle Press published his Fish Tales: Shipping Out & Millwork. I had the clip about his books for years and years in a drawer of my nightstand, intending to buy Al’s books and read them. However, I could never get sufficiently motivated. I had read, much earlier, Isaac Bashevis Singer’s wonderful Jewish family sagas, and I believe I knew that Al’s books could never compete with Singer’s wonderful stories.

I was a bit taken aback when I understood that Al expected us to put him up with his child-wife, which no other former colleague had asked us to do. So grey-haired, fiftyish Al had found himself a young girl who was a bit younger than his two sons. Well, what else is new?

I picked them up at Orly airport, as they arrived from the girl’s family’s home in Bretagne. The new Charles de Gaulle airport, which has become one of the major hubs in Europe, had not opened yet in the late 70s, when this took place. Before picking them up, I had been wondering, being at heart quite a bourgeoise, what I might offer them right away as we got to our apartment. I had settled for a glass of sherry and that worked out fine.

We had a nice time with Al and his child-wife, but I have no idea how that strange marriage turned out. A young French girl from Bretagne marries an American intellectual Jew who could easily have been her father, and whose wife, this is my guess, had just killed herself. I can see no other way that makes sense that this horrible “accident” could have happened.

I have now found out that Al was treated for cancer in the 80s and that he died at the end of the decade. Far too young.

Continued: Chapter 18 – (Part 2) ; Mamaroneck High School theater

Sillitoe